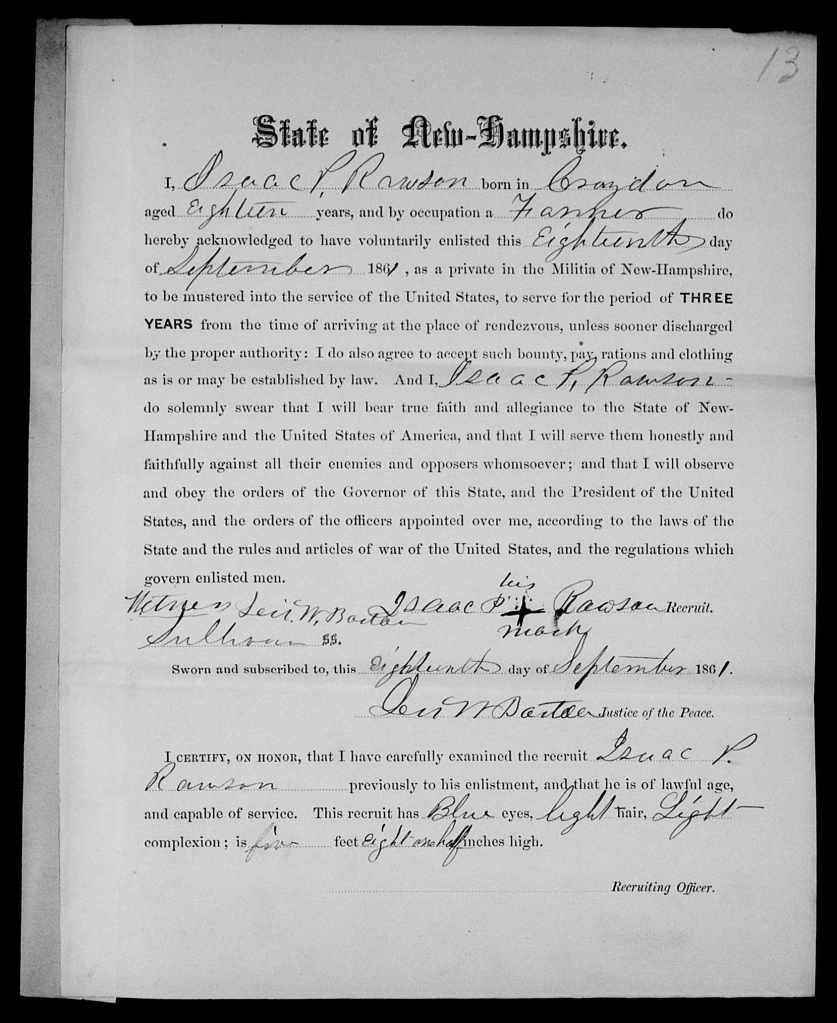

Enlistment Form for Isaac P. Rawson (1861): Rawson, who was presumably illiterate, made “his mark” on this enlistment form. Levi Barton, who signed the form as a Justice of the Peace, also witnessed Rawson’s mark. Barton was the father of Ira Barton, who became the Captain of Company E, in which Rawson served. Rawson was only 16 when he enlisted.

It’s possible that I’ve overlooked some books and articles, but a brief search of works on the Civil War indicates that scholars have not spent much time thinking deeply about soldier literacy. A number of historians have trotted out the figure that 90% of Union soldiers were literate and made the argument that the conflict “was fought by the most literate soldiers in history” (to quote James McPherson).[i] Who arrived at this figure and how it was arrived at remain a mystery to me. Just as important, none of these historians has attempted to define just what he or she means by “literacy.”

Among my pool of 540 original volunteers in the 5th New Hampshire, I found 409 enlistment forms where a volunteer was called upon to sign his name. In only 34 cases were they unable to do so (a percentage of 8.3%). But it appears from many of the signatures I saw that large numbers of men had only the barest familiarity with pen and paper (see below for examples from 5th New Hampshire enlistment forms). And that forcibly brought to mind the following point: literacy exists on a spectrum, and not all volunteers who could sign their names were equally capable of reading and writing. Or to put it another way, many men who could sign their names were probably functionally illiterate.

Albert Eastman

Harvey Perry

Jabez McDuffee

Stephen Maxfield

Walden Cross

That fact raises the question of what the word “literate” means and what the spectrum of literacy looks like. There is no universal standard for what passes as literacy, but the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has defined levels of literacy that have become fairly prevalent. UNESCO has also generated the following definition of literacy:

Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.

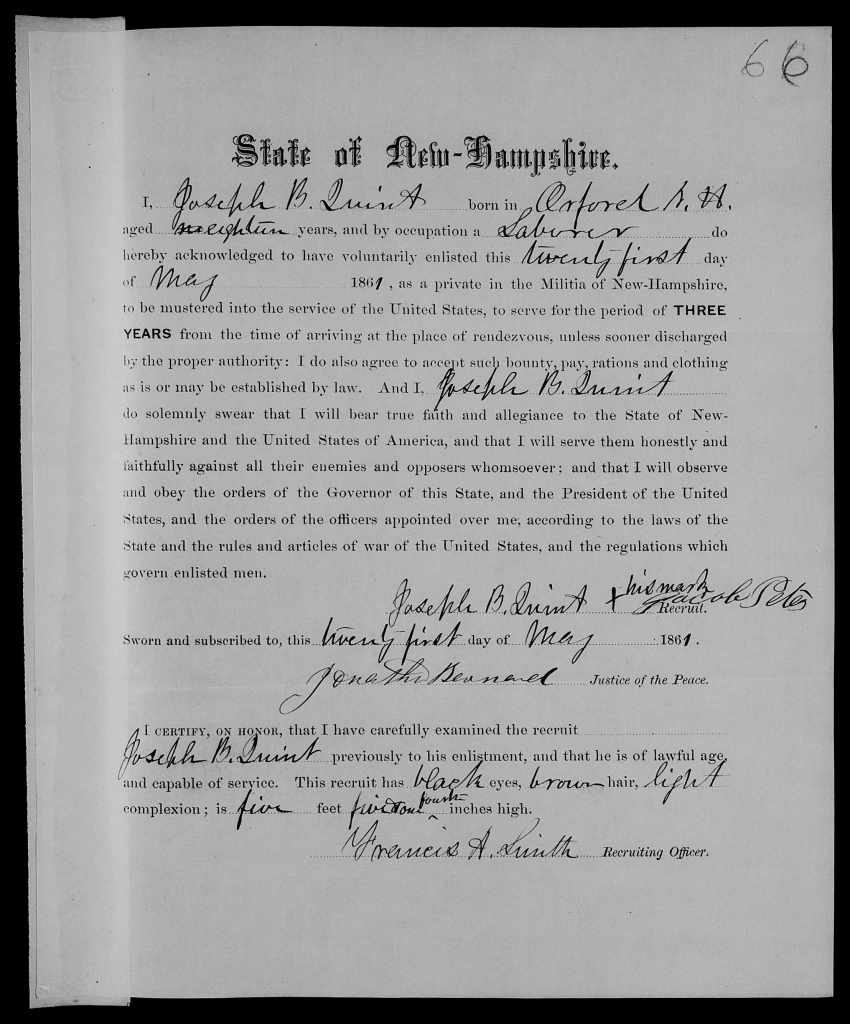

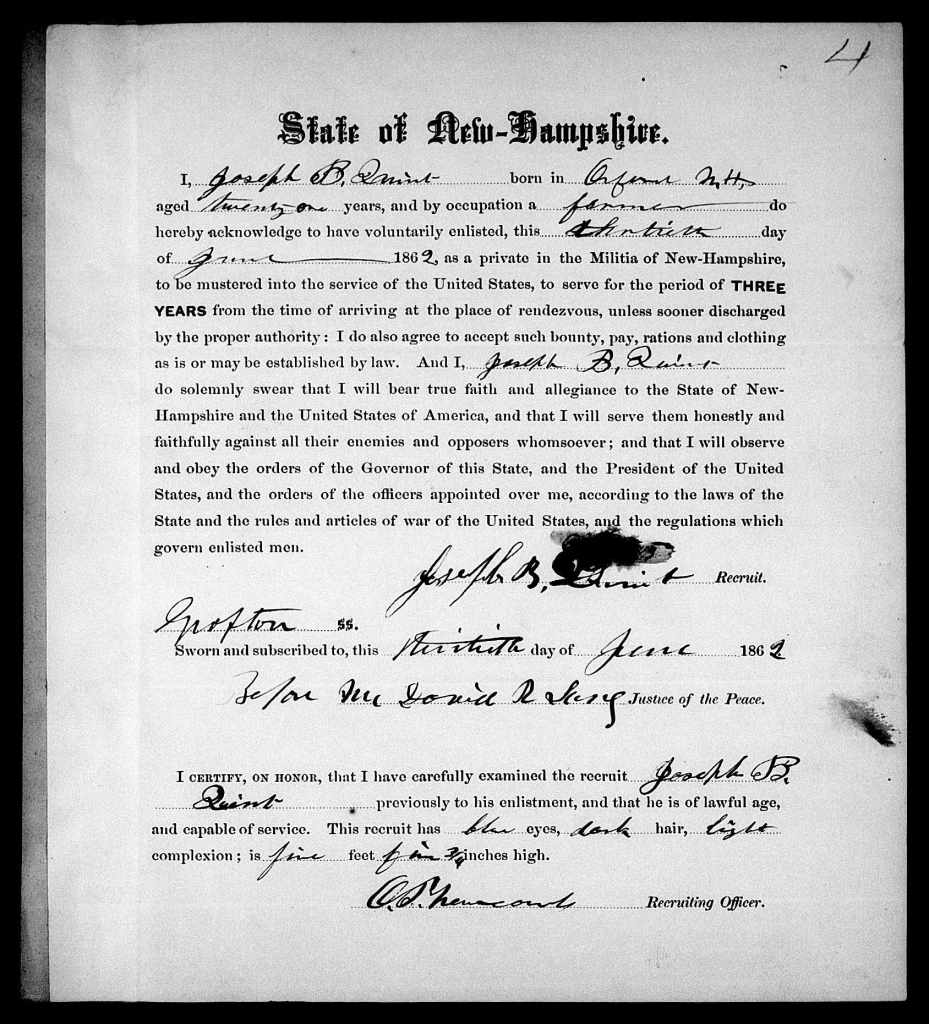

The problem with many contemporary definitions is that they are either fairly general or culturally specific. In the former case, they provide very little precision for assessing literacy in the mid-19th century, and in the latter, they are not applicable. Another problem in studying this topic is that literacy is fluid; a person can either gain or lose it. Joseph B. Quint is a good example of this fluidity. In May 1861, when he enlisted in the 1st New Hampshire, he could not sign his name. Only four months later, in September 1861, when he volunteered for the 5th New Hampshire, he could (he was discharged in October, however, on the recommendation of Assistant Surgeon John Bucknam because of a “Lung difaclity” [sic]).[ii]

From left to right: Jacob Quint’s enlistment form for the 1st New Hampshire (May 1861); Quint’s enlistment form for the 5th New Hampshire (September 1861); Quint’s enlistment form for the 9th New Hampshire (June 1862).

Although studying illiterate and semi-literate soldiers is plagued with difficulties, not least of which is locating primary source materials, it seems to me that Civil War historians have treated this topic superficially by assuming that the vast majority of the Union army’s rank and file was simply “literate.”

In the rest of this post, I’d like to launch a brief investigation of the experience of illiterate soldiers by looking at the 34 men in my sample who couldn’t sign their names. As I do so, it makes sense to keep two things in mind. First, the sample size is very small, so we should not leap to any dramatic conclusions about illiterate soldiers. Second, we should also resist the temptation to attribute all the distinctive features of this group to an inability to read and write.

On average, the illiterate men were about almost three years older (27.9 years) than the regiment as a whole. This average, though, conceals a strange distribution: six of the soldiers were underage (under 18) while four of them were overage (over 44). That means the proportion of men who were not of legal age was two times higher among illiterate soldiers than it was in the regiment as a whole. I don’t know what to make of that or if it’s significant, so let’s move on.

I was able to determine the family status of 25 of the 34 men in 1860. Nine were heads of household (plus a single man living with a railroad gang); the rest lived with their parents or in someone else’s household. That’s similar to the rest of the regiment, so nothing to see here.

In seven instances, I found out the occupations of these men’s fathers in 1860. Two were laborers and five were farmers. Not surprisingly, the laborers had no money to speak of, and in every case but one, the farmers possessed very little property, with real estate amounting to $800 or less. So there is, perhaps, some small correlation between illiteracy and poverty (although many sons of laborers and small farmers were literate).

Starting as early as 1880, the census bureau began wrestling with how to define an urban area, and it started labeling incorporated areas of 2,500 or more as “urban” in 1910.[iii] If we apply this standard to the United States in 1860 (yes, I know that’s anachronistic), we find that nine of our illiterate soldiers hailed from urban areas:

- Concord, NH (1)

- Dover, NH (4)

- Claremont, NH (1)

- Portsmouth, NH (1)

- Lowell, MA (1)

- Gilford, NH (1)

That means 26% of the sample came from an urban area. The corresponding figure for the 5th New Hampshire was 24% and for the state of New Hampshire, 26%. So whether a man lived in town or country seems to have made no difference at all.

In 29 cases, I found what our illiterate soldiers’ occupations were in 1860:

- Farm laborer (15)

- Day laborer/Laborer (8)

- Mule spinner (1)

- Railroad laborer (1)

- Blacksmith (1)

- Carpenter (1)

- Shoemaker (1)

- Weaver (1)

This list skews toward unskilled manual labor—there aren’t as many shoemakers, carpenters, and farmers on this list as you might expect to find in a random sample of the 5th New Hampshire. I suppose that should come as no surprise since these men were illiterate.

These men’s reasons for leaving the regiment were not at all out of the ordinary.

- 19 obtained disabled discharges

- 3 were transferred to another unit (one to the US Navy, and two to the Invalid Corps/Veterans Reserve Corps)

- 3 were killed in action (Savage’s Station, Gettysburg, and Deep Bottom)

- 3 were mustered out (two after three years, one at the end of the war)

- 2 died of disease

- 2 deserted

- 1 was mortally wounded (Gettysburg)

- 1 has no record of how, when, or why he was discharged

According to Ayling’s Revised Register, these 34 men suffered 18 wounds in combat (which is most certainly an undercount). On average, they served 17 months with the regiment. All of this is par for the course.

I was also able to find out in 30 cases whether these men had married at any point in their lifetime, and 90% did—which, again, is pretty much the same as the rest of the regiment. It’s worth noting here that several men who never married died in the service while still in their twenties.

In 21 cases, I was able to figure the highest occupation that these men attained over the course of their lifetime:

- Farmer (6)

- Carpenter (4)

- Laborer (4)

- Soldier (1)

- Blacksmith (1)

- Farm laborer (1)

- Railroad brakeman (1)

- Peddler (1)

- Mechanic (1)

- Shoemaker (1)

When compared to the attainments of other veterans of the 5th New Hampshire, this list is not terribly impressive, but for men who mainly started in unskilled work and could not read, it’s not bad. And one wonders if some of these men eventually picked up literacy over the span of their lives.

The average lifespan of this group was surprisingly high: 69 years. This figure compares very well with the regiment as a whole. Six men lived into their 70s, seven died as octogenarians, and one made it well into his 90s.

Thus far—and inasmuch as numbers can tell us—it appears that on paper (for numbers reveal little about the qualitative experience of illiteracy), illiterate soldiers in this pool resembled their more educated comrades. The one exception seems to be that as young men, they had a tendency to work in unskilled occupations. Their general lack of job skills and their illiteracy may have conspired to prevent them from rising as far as their better read comrades.

But there is one area where the experiences of men who could not read or write contrasted dramatically with the rest of the regiment. Not a single illiterate man in the group attained noncommissioned rank (let alone a lieutenancy or captaincy). When my group of 34 men were mustered in, 33 entered the army as privates and one as a musician. All of them left the army holding the same rank with which they had entered. This situation calls to mind an anecdote that Thomas Livermore relates about Corporal Daniel Harrington in Days and Events:

He was a tall, straight, rosy-cheeked Irishman, a model soldier and as clean as could be, but could not write. He had been made a corporal for soldierly conduct, and I had taken him as a bunkmate, he being a willing helper about my duties and a good comrade. His ambition for promotion was excited by his corporal’s chevrons, and I recollect that one night when we lay in bivouac, our blankets rolled around us, and the stars twinkling in our faces, he roused me with “Orderly!” “What?” “Did ye iver know a sarjint that could n’t write.'”‘ “Yes, corporal”; and with a word or two of encouragement I went to sleep.[iv]

According to Ayling’s Revised Register, Harrington became a corporal in April 1862. Wounded at Fair Oaks in June 1862, he was discharged disabled in August that year. He re-enlisted in the 5th New Hampshire in April 1864 and was wounded again at Cold Harbor in June. He later transferred to the Veterans Reserve Corps in October 1864. And he never obtained his sergeant’s stripes.[v]

Daniel Harrington’s Enlistment Form (1861)

Harrington’s experience seems to be the exception to the rule; illiterate men were usually not promoted to corporal. They couldn’t keep the books, call roll, or read written orders. But the stigma went beyond that. Northerners, particularly New Englanders, saw literacy as a badge of their superior civilization. For that reason, they must have found illiterate soldiers embarrassing because these men had somehow “let the side down.”

Livermore’s reassurances to the contrary (it cost him nothing to issue them), Harrington clearly understood that his inability to write was a bar to further promotion. Moreover, as a poor Irishman, a laborer, and an illiterate, Harrington must have instinctively realized that he suffered from a mid-19th century intersectionality that served as an obstacle to his ambitions. All of these markers could not be hidden—including his illiteracy, which necessitated the calling of a witness when Harrington made his mark on an enlistment form.[vi] But it would be his inability to write that served as the primary excuse for not promoting him.

In any event, it appears that one big difference between men who could read and write and those who couldn’t was that the latter had very little hope of receiving a promotion. But bringing this post back full circle, what about the men who could sign their names but possessed subpar reading and writing skills? Did they, too, experience difficulty in earning promotion? In other words, did widespread low-level literacy (as opposed to illiteracy) disqualify large numbers of men from noncommissioned rank in the Union army during the Civil War?

[i] See Christopher Hager, “The Literate War/The Literacy War” Mississippi Quarterly 70:4 (January 2017), 411.

[ii] Quint eventually found his way into the 9th New Hampshire. He died of disease in April 1863 at Point Lookout, MD. “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2Q1-BHQQ : 16 March 2018), Joseph B Quint, 21 May 1861; citing New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,257,028.; “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2Q1-YNRZ : 16 March 2018), Joseph B Quint, 14 Sep 1861; citing Grafton, Grafton, Grafton, New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,217,641.; “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2Q1-YNBY : 16 March 2018), Joseph B Quint, 14 Sep 1861; citing New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,217,641.; “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2Q1-Y2P7 : 16 March 2018), Joseph B Quint, 30 Jun 1862; citing Grafton, Grafton, Grafton, New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,217,660.

[iii] https://www.census.gov/history/www/programs/geography/urban_and_rural_areas.html; https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/GARM/Ch12GARM.pdf

[iv] Thomas Livermore, Days and Events 1860-1866 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920) 54.

[v] Augustus D. Ayling, Revised Register of the Soldiers and Sailors of New Hampshire in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1866 (Concord: Ira C. Evans, Public Printer, 1895), 239,

[vi] “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2Q1-YD6Z : 16 March 2018), Daniel Harrington, 01 Oct 1861; citing New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,217,641.