Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field (1865)

Winslow Homer, Francis Barlow, and Two Degrees of Separation from the 5th New Hampshire

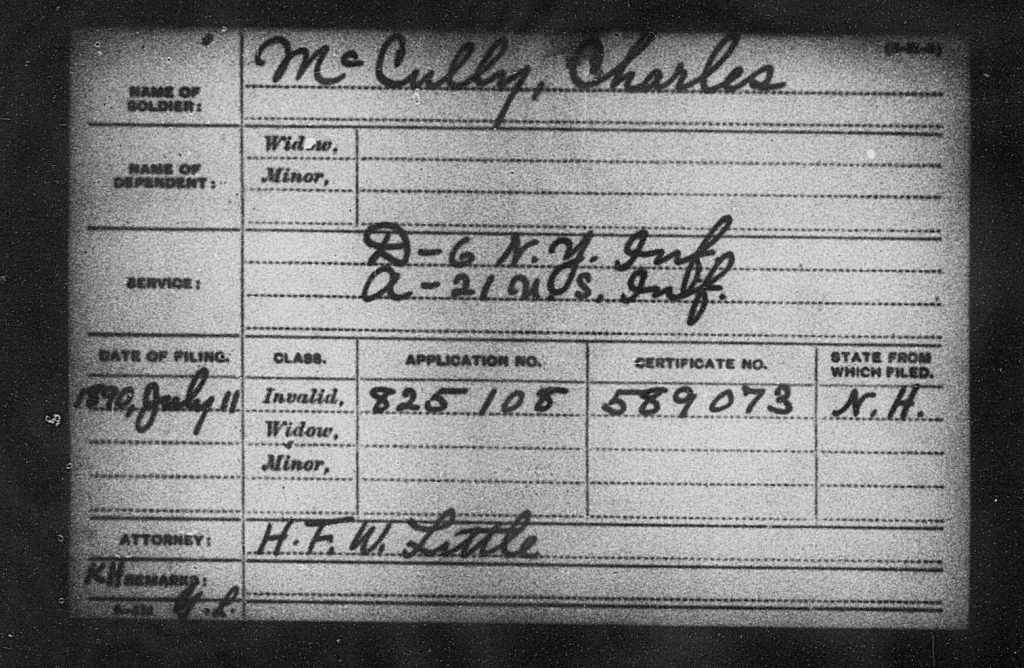

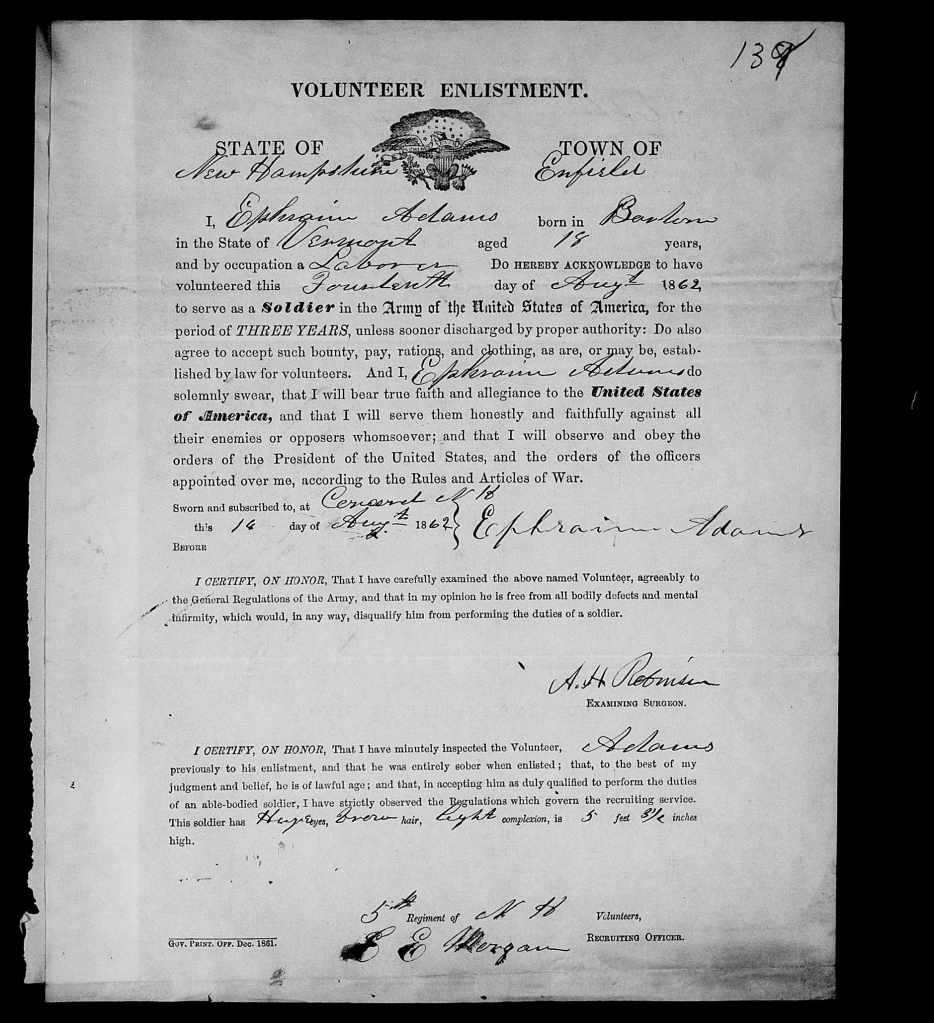

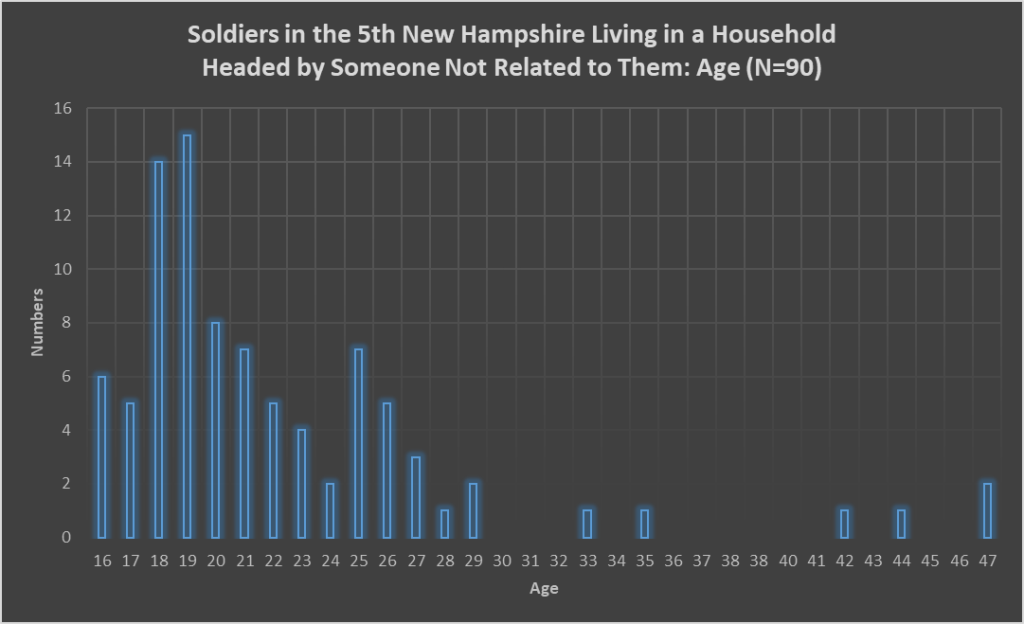

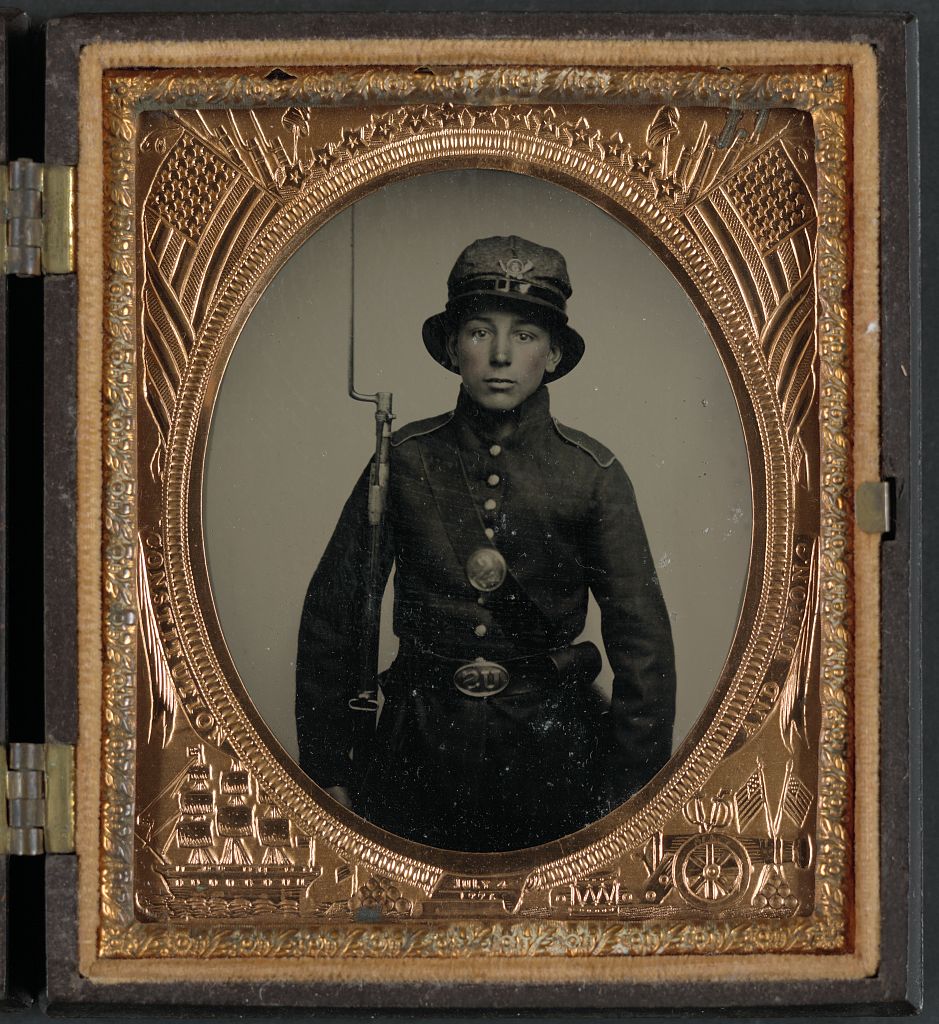

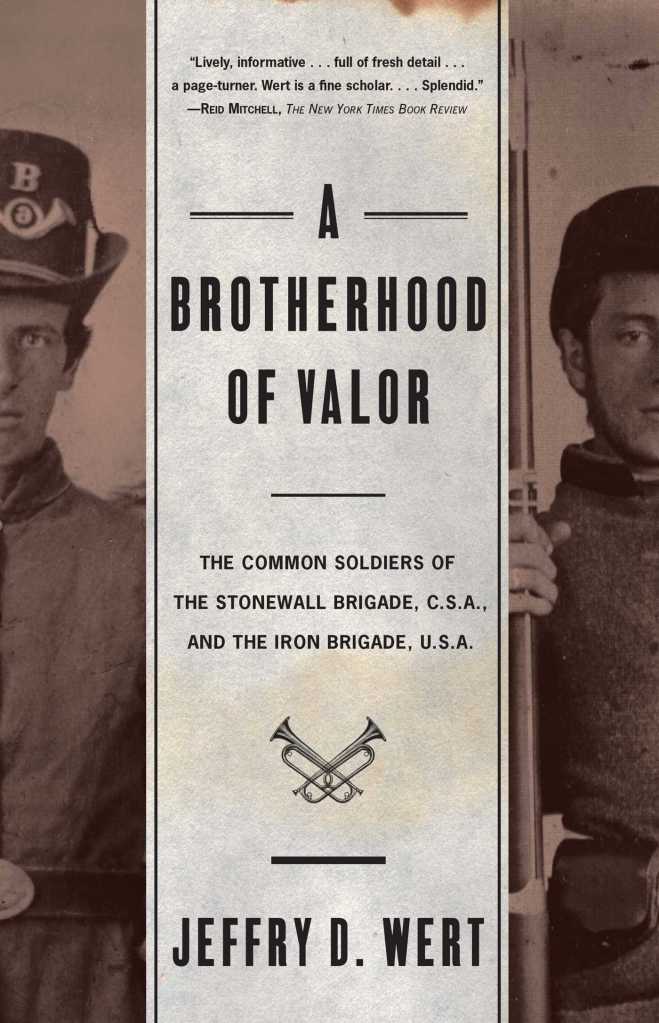

Today, I thought I’d do something different by discussing what I find to be one of Winslow Homer’s most moving works. How shall I justify this choice of topic? In other words, what does this have to do with the 5th New Hampshire? Homer was Francis Barlow’s cousin. Yes, that Barlow–the famous Union “boy general” who was the scourage of stragglers. Small world, isn’t it? Early in the war, Barlow was the colonel of the 61st New York which was brigaded with the 5th New Hampshire. Shortly after the Battle of Antietam, he left his regiment to assume command of a brigade which was the first step in his march to fame. Later, in 1864, he became commander of the 1st division in II Corps which is where the brigade containing his old regiment and our Granite Staters fit in the Army of the Potomac’s order of battle.

Winslow Homer, Prisoners from the Front (1866)

Any of you familiar with the Civil War and Winslow Homer knows the artist placed his general-cousin in one of the most important paintings generated by the conflict, Prisoners from the Front (1866) (to which the movie Gettysburg paid an awkward homage). This should come as no surprise. When Homer visited the Army of the Potomac, sometimes, but not always, as an artist-correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, he would avail himself of Barlow’s hospitality and stay with the 61st New York. If you look closely at the painting, you’ll see on the right margin a flag with the red trefoil of the 1st division, II Corps–Barlow’s division starting in 1864. And the Union soldier guarding the prisoners also sports a red trefoil on his forage cap—along with a brass “61” denoting his membership in the 61st New York.

Winslow Homer, Prisoners from the Front (1866) (details): The red trefoil of the 1st division, II Corps is everywhere!

In Prisoners from the Front as well as contemporary photos, Barlow looks like a genteel, fresh-faced boy who could have studied law at Harvard alongside the scions of Boston Brahmins (which he did). In this case, though, appearances are completely deceiving. Barlow was painfully blunt and fearless to the point of utter recklessness. He was also an iron disciplinarian. He became one of the North’s great division commanders of the war and helped II Corps win its reputation as the anvil of the Army of the Potomac.

But enough about Barlow. What of Homer and his painting?

Leaders of the II Corps (1864): These were the men who pushed II Corps through the Overland Campaign that drove the Army of Northern Virginia back to Petersburg. The exhaustion of this task is evident from their faces. Standing from left to right are Brigadier General Francis Barlow (1st division), Major General David Birney (3rd division), and Major General John Gibbon (2nd division). Seated is Major General Winfield Hancock (commander of II Corps).

The Mixed Messages of The Veteran in a New Field

The Veteran in a New Field is a great work of art. If you don’t agree, I hope at least you’ll understand why I like it so much. At first glance, the painting seems awfully simple. It depicts the sky, some wheat, a man, and his scythe. If you search the canvas a little more, you’ll find a cast-off jacket atop which lies a canteen. The simplicity of the composition provides the painting with much of its power. Yet The Veteran in a New Field is also intriguing because of its nuance, ambiguity, and contrasts. Through various symbols, the painting conveys a number of subtle messages, some of which complement and contradict one another. Finally, we must consider context; it’s hard to measure the force of this work unless we imagine it as a product of the immediate post-war era (various sources date the work to somewhere between April and October 1865).

Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field (1865) (detail)

Scholars have often claimed this work presents a national narrative. That is, the painting is about Northern victory, American regeneration, and so on. But I prefer to focus on the idea of the veteran. The title of the painting suggests the veteran is not literally harvesting a new field but that he has embarked on a new type of endeavor. Instead of the battlefield, he has moved on to the wheat field which signifies his embrace of peaceful pursuits. In 1865, the majority of Americans still earned their living from the land, and wheat was replete with symbolism for them. For one thing, unlike cotton, which was tainted with slavery and secession, wheat was a good, honest Northern crop (although it must be conceded that at this point, corn was the predominant cereal crop in New England). Wheat had long been associated with regeneration and fertility, so the mowing here speaks to hope for the future. These associations were closely related to the Parable of the Grain of Wheat (John 12:24-26):

Verily, verily, I say unto you, еxcept a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal. If any man serve me, let him follow me; and where I am, there shall also my servant be: if any man serve me, him will my Father honour.

The parable suggests that like wheat left on the stalk, we must die. And we must accept our death before we can be reborn a true servant of Christ. Only then can we attain the Kingdom of Heaven. As the Apostle Paul stated in Corinthians 15:42, “What is sown in the earth is subject to decay, what rises is incorruptible.” The parable was also a metaphor for Christ’s own death and resurrection. What Homer seemed to imply was that America had been reborn only because hundreds of thousands of the North’s sons had sacrificed themselves to purify the country. In contemplating the Parable of the Grain of Wheat, I’m reminded here that the 61st New York, Barlow’s old unit, fought in the Wheatfield during the second day at Gettysburg. Bled white by two years of service, the regiment brought into action “only 90 muskets” of whom 65 were killed or wounded.

61st New York Monument in the Wheatfield at Gettysburg National Military Park

And that bring us to the veteran’s farming implement. Our veteran swings what contemporaries would have considered an archaic scythe. This was not a mistake on Homer’s part; it was a deliberate choice. If you look closely at the painting, he originally included a grain cradle on the scythe that would have brought it up to date. That Homer painted over the grain cradle indicates he reached for associations with the grim reaper who mowed men down with a traditional scythe. This metaphor of mowing men came naturally to Civil War soldiers, a majority of whom were farmers or farm laborers. At close range, volleys had a tendency to knock entire ranks of soldiers down like “wheat before the scythe” as the saying goes. In The Veteran in a New Field, the titular character is mowing wheat instead of men, but does the metaphor occur to him at this moment?

Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field (1865) (detail)

What The Veteran in a New Field is Doing

What our veteran thinks as he mows his wheat is impossible to say. Because his back is turned to the viewer, he remains an enigmatic figure. Does he feel hopeful about a prosperous future? Is he traumatized and damaged by his wartime past? Who knows? The veteran’s back is turned to us, so we cannot read his expression. What accentuates the enigma here is that the veteran is also liminal. He is neither soldier nor civilian; he is a veteran. Unlike the soldier, he no longer serves in the army. Unlike the civilian, he knows what only a soldier who has seen combat can know. The veteran has taken off his old army jacket and canteen (which, by the way, bears the red trefoil of the 1st division, II Corps). But they still remain in sight, and he wears his army-issued pants. Commentary from one art historian I read pointed out that mowing was communal work, but, here, the veteran swings his scythe alone. He stands, thus, for all veterans, a unique class of men set apart from others. It occurs to me that as he toils, he is working out his future.

Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field (1865) (detail): The veteran’s jacket lies on the ground in the bottom right-hand corner of the canvas. It appears to be the Union army’s standard-issue four-button sack coat. Atop this jacket lies an army canteen with the red trefoil of the 1st division, II Corps and the initials “W. H.”

These ruminations remind me of an important scene in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) one of the finest American films about veterans returning from war (in this case, it’s World War II). Toward the end of the movie, one of the main characters, Fred Derry (played by Dana Andrews), a former USAAF bombardier who suffers from PTSD and carries a chip on his shoulder the size of a Cadillac, has “a moment.” His marriage has collapsed, he’s lost his job as a soda jerk, and the woman he loves is unavailable. The contrast between his life as a bombardier, when he was a hero, and his failures as a civilian are too great for him to bear. He vows to leave his hometown of Boone City. While waiting for a flight to take him away from the scene of his failures, he walks, ironically enough, through an aircraft boneyard filled with B-17s of the type that he flew over Europe. He clambers into the nose cone of one of these bombers, goes into trance, relives his horrifying wartime experiences, and undergoes some sort of catharsis. When Derry emerges from his daze, he isn’t exactly a new man. The movie is too nuanced to do something like that. What is clear, though, is that he is now determined to do his best to put the war behind him and make the most of his situation.

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) (still)

I imagine the veteran in Homer’s painting is doing the same thing. While working in the field, he is also working out his future. Neither the civilian nor the soldier can help him determine his fate; that is why he is alone in the new field. Will memories of a red-sodden past prevent him from realizing a golden and bountiful future? In other words, will his experiences of a time when men were scythed like wheat make it impossible for him to scythe wheat like men? As the veteran weighs his options, all we can hear is the scratch of the scythe gliding through the wheat. But does the veteran hear the same thing? Or does he remember the weighty buzzing of Minié balls and the strange sound they made as these projectiles splattered upon meeting human flesh?

Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field (1865) (detail)

What I appreciate about this painting is that it doesn’t possess the treacly sentimentality that characterized most contemporary representations of the soldier’s homecoming. It is ambiguous and even, perhaps, ambivalent. What I also find interesting is that many art critics at the time disapproved of Homer’s style, which they described as unfinished. This criticism reminds me of the way art connoisseurs reacted to Edouard Manet’s technique in his groundbreaking Olympia, which paved the way for the Impressionists. But Homer’s approach to painting (like Manet’s) was entirely appropriate. In 1865, veterans were incomplete and works in progress. Only time would tell what and who they would become.