Jonathan C. S. Twitchell (1834-1910): When he enlisted in 1861, Twitchell was a lumberman and millman living in his father’s household in Drummer, NH. At 27 years old, Twitchell was a bit older than most volunteers who still lived at home with their parents. But he was also typical in that his father, Ransom Twitchell, a farmer, had amassed an estate of almost $3000; soldiers who still lived with their parents tended to come from wealthier households. Starting out as a private, Twitchell was eventually appointed Captain of Company K in October 1864. This image shows him with the chevrons of a 1st Sergeant. He served with the 5th New Hampshire until the end of the war and was wounded only once (in the right leg). After the war, he married (1866), moved around a bit, and eventually ended up in Stonehouse, VA, where he worked as a grocer. (This carte de visite and the others displayed in this post are courtesy of David Morin.)

You never know where the data you collect will lead you, and the household status of soldiers in the 5th New Hampshire is a case in point. When I amassed information from the 1860 Census about the people with whom volunteers were living, I never imagined such stark patterns would emerge So, without further ado, let’s go look at the statistics. Yes, I’m afraid there will be lots of numbers in this post.

Varieties of Households

In my pool of 540 soldiers who enlisted in the 5th New Hampshire in September and October 1861, I found the household status of 423 men by using the Census of 1860. The results are below:

- 155 lived in households headed by their fathers

- 141 were the heads of their own households

- 91 lived in households headed by people unrelated to them.

- 13 lived in households headed by their mothers

- 11 lived by themselves in various arrangements

- 9 lived in households headed by their siblings

- 1 lived in a Shaker community

- 1 lived in the town poor house

- 1 lived with his uncle

All of these situations interest me, and I could find something intriguing to say about all of them, but I’d like to focus on the three most common arrangements because they account for 91% of the men in the regiment.

Soldiers Living in Households Headed by Their Fathers (N=155)

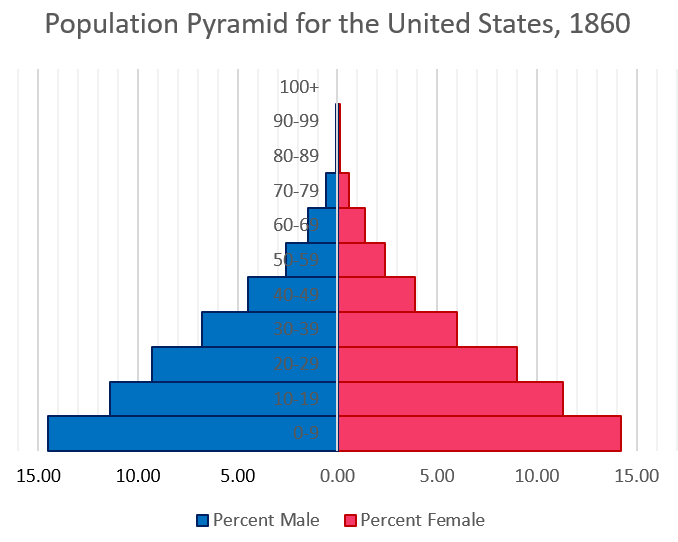

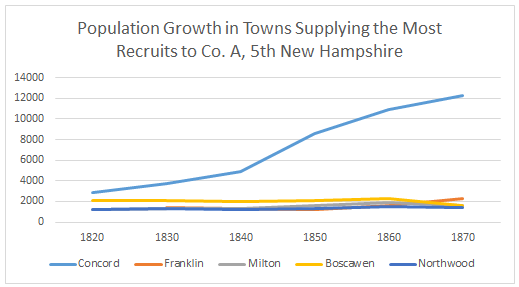

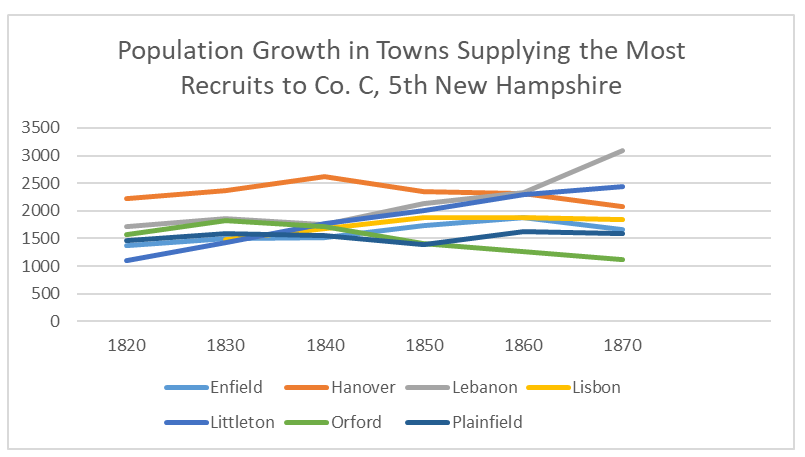

Not surprisingly, this group, on average, was the youngest of the three (20.3 years old). The median age was 19. Like the other two groups I’ll be discussing, this one was relatively evenly distributed among all the 5th New Hampshire’s companies (although A and F were a bit on the short side).

This graph mirrors the overall profile of the regiment (see here). That surprised me somewhat; I would have thought this group would have been even younger since, after all, it was living at home with parents. What is not surprising is the drop off in numbers at 24; it was usually at this point that young men got married and left home.

This was also the wealthiest of the three groups. If we look at the estates of these men’s fathers, we see that they were relatively well-off (for the total value of the estate, I added personal and real estate as indicated by the Census of 1860).

Farmers dominated among the fathers of these soldiers, making up just over 60% of the group (n=147). The value of most farms fell somewhere between $1500 (which seems to have constituted the minimum for a viable concern) and $4000. The prevalence of skilled labor, white collar workers, professionals, and owners of capital account for the wealth of these men.

- Farmer: 89

- Laborer/Farm Laborer/Day Laborer: 18

- Carpenter: 7

- Mechanic: 4

- Physician: 3

- Lawyer: 3

- Trader/Merchant: 2

- Marble Worker: 2

- Teamster: 2

- Cordwainer: 2

- Blacksmith: 2

- Iron Machinist: 2

- Mason: 2

- Millwright: 1

- Box Maker: 1

- Iron Manufacturer: 1

- Shoemaker: 1

- Painter: 1

- Joiner 1:

- Crockery and Looking Glass [Manufacturer]: 1

- Bridge Builder: 1

- Real Estate Broker: 1

- Stone Cutter: 1

- Miller: 1

- Tailor 1:

- Bank Cashier: 1

Keep these numbers in mind as you look at the other groups; the contrast is shocking.

Thomas Folsom (1827-1863): Folsom was fairly typical of the heads of household who served in the 5th New Hampshire–he was older, married, a father, and man of small means. Born in Gilmanton, NH, whose population had been shrinking for decades, he married Mary Frothingham in 1850. By the time he enlisted, he had a seven-year-old son named George. According to the Census of 1860, Folsom still lived in Gilmanton, working as a day laborer with an estate that totaled $300. He was shot in the thigh at the Battle of Fair Oaks (June 1861) and mortally wounded at Chancellorsville (May 1863), dying three weeks later.

Soldiers Who Were Heads of Households (N=141)

Without looking at the figures, I would have guessed that this group was relatively young (20s and early 30s) with a little bit up capital saved up. And I would have been way off the mark.

The average age of these men was a stunning 34.4 years old.

- 51 were in their 20s

- 55 were in their 30s

- 24 were in their 40s

- 11 were in their 50s

Men in their 20s, who were probably the best suited for soldiering, formed just over a third of the group. Moreover, on average, the economic prospects of these heads of household did not look terribly good, especially when you consider they had enjoyed ample time to accumulate capital.

I found the value of the estates of 110 of these men, and they look as follows. (Please compare with the fathers of the men who were still living at home in 1860.)

The occupations of this group make it very clear why it was not as wealthy as the fathers of soldiers still living in their parents’ households.

- Shoemaker: 37

- Laborer/Farm Laborer/Day Laborer: 36

- Farmer: 15

- Factory Operative: 5

- Machinist: 4

- Blacksmith: 4

- House Carpenter: 4

- Joiner: 3

- Tailor: 2

- Cordwainer: 2

- Brick Mason: 2

- Coachman: 1

- Stone Mason: 1

- Stone Cutter:1

- Saw Mill Laborer: 1

- House Painter: 2

- Shoe Cutter: 1

- Booking Agent: 1

- Stage Driver: 1

- Printer: 1

- Clergyman: 1

- Railroad Laborer: 1

- Music Teacher: 1

- Ornamental Painter: 1

- Cabinet Maker: 1

- Worm Cutter: 1

- Tanner: 1

- Peddler: 1

- Bit and Augur Maker: 1

- Basket Maker: 1

- Merchant: 1

Like the soldiers still living in their fathers’ households, this group was fairly evenly distributed among all the regiment’s companies (although they were overrepresented somewhat in A, D, G, and especially the band).

A poor man can be just as patriotic as a wealthy one, but in this case, one wonders if the financial motive for enlisting was somewhat stronger with this group. In the fall of 1861, bounties had not even begun to approach their stratospheric 1863 and 1864 levels. However, a number of these men, who must have suffered from the economic downturn associated with the Panic of 1857, may have thought that the prospects of army life, which included “three squares” a day and $13 per month, were attractive. Certainly, something important must have attracted these men. They left behind wives and children, thereby sacrificing a great deal more by leaving home than their younger, unmarried comrades did.

Henry McGann (1843-1919): Born in Bangor, ME, McGann found himself in Cornish, NH, in 1860, living and working on the farm of Nathaniel Pease, whose total estate amounted to about $2300. This was a common pattern among volunteers who lived in a household headed by someone not related to them; more often than not, these men were farm laborers who lived with their employers. McGann’s service record indicates he was a brave soldier. He was wounded three times–at Fair Oaks (June 1862), Fredericksburg (December 1862), and Farmville (April 1865). A pension payment form from 1888 mentions that he suffered from ““G. s. wds. r. knee & face” [gunshot wounds to the right knee and face]. McGann was appointed Sergeant and re-enlisted in 1864, serving until the end of the war. Here, however, he sports the chevrons of a Corporal. Original volunteers like McGann who later became NCOs seem to have been the glue that held the regiment together in the last 18 months of the conflict, when the rank and file consisted mainly of foreign-born substitutes. After the war, McGann appears to have been involved in the lumber industry for some time. He was married at least three–if not four–times. He ended his days at the New Hampshire Soldier’s Home in Tilton, NH.

Soldiers Living in Households Headed by Someone Not Related to Them (N=91)

I feel a little diffident making definitive statements about these men for several reasons. First, it’s not always easy to determine if people living in the same household are not related. Second, since these soldiers were not heads of household, I worry that census takers may have overlooked whatever personal property these men had acquired (only nine are listed as owning any property at all). Third, since it’s not clear who their parents were (as opposed to the soldiers who lived with their parents), it’s impossible to establish their class background.

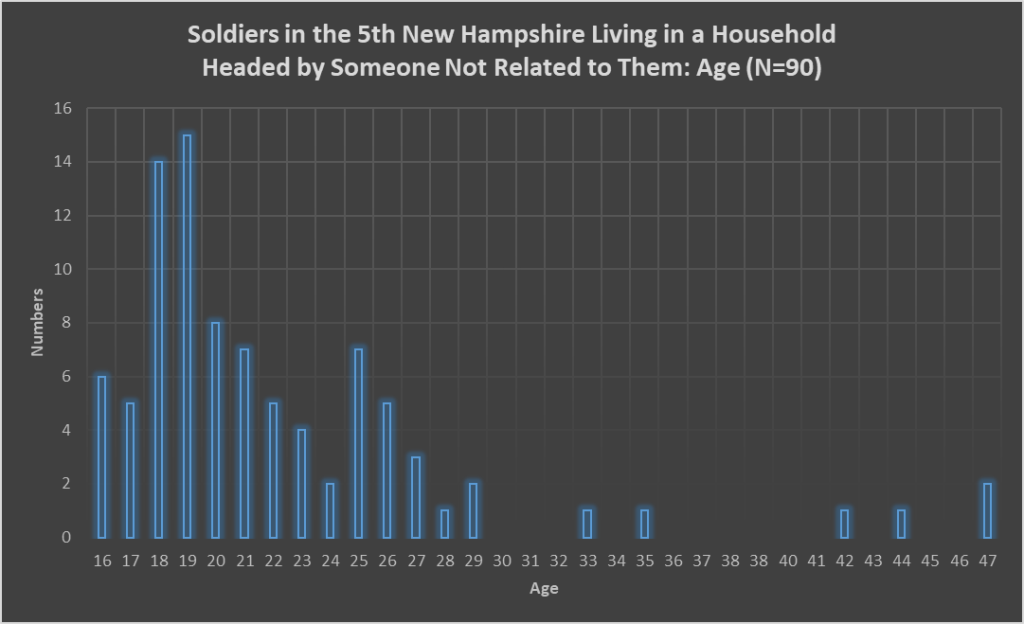

Since these men did not head their own households, they too were fairly young (average age was 22.2 years old, median age was 20). Their age profile, however, is somewhat different from the soldiers who lived in their fathers’ households. This is largely the case because there are a number of older men who were farm laborers who appear to have lived with their employers who were farmers (more about that later).

The age profile is as follows:

I found occupations for 83 of these men. The distribution of occupations is as follows:

- Farm Laborer: 43

- Shoemaker: 5

- Farmer: 4

- Clerk: 4

- Cordwainer: 2

- Physician: 2

- Carpenter: 2

- Painter: 2

- Glass Bottle Converter: 1

- Teacher: 1

- Looking Glass Man: 1

- Millman: 1

- Machinist: 1

- Student: 1

- Mechanic: 1

- Stone Cutter: 1

- Sash and Blind Maker: 1

- Hostler: 1

- Currier’s Apprentice: 1

- Weaver: 1

- Sawing: 1

- Factory Operative: 1

- Sailor: 1

Almost all of the laborers appear to have lived with their employers who were farmers. Many of the other men seem to have lived with their employers or boarded with a family for convenience’s sake.

A Final Experiment

For the heck of it, I used a simple measurement to compare the war experience of these three groups. What proportion of them died during the war, and what exactly did they die from? Here’s what I found.

Soldiers Living in Their Father’s Households (n=155):

- 17 killed in action (11% of total)

- 5 suffered mortal wounds (3% of total)

- 21 died of disease (14% of total)

Over a quarter of this group died in the service (28%) with the total evenly split between combat and illness. This was the only group where such was the case; in the others, more men died from combat than disease.

Soldiers Who Were Heads of Household (n=141)

- 10 killed in action (7%)

- 10 suffered mortal wounds (7%)

- 7 died of disease (5%)

Almost a fifth of this group died in the service (19%) with 5% dying of disease and 14% dying in combat. This group suffered an unusually low number of deaths from disease.

Soldiers Living in a Household Headed by Someone Unrelated to Them (n=91)

- 16 killed in action (21%)

- 5 suffered mortal wounds (5%)

- 10 died of disease (11%)

Over a third of this group died in the service (34%) with 11% dying of disease and 26% dying in combat. This group experienced the highest overall mortality, largely because it suffered far more from combat than the other groups.

Each group underwent distinct experiences during the war. Soldiers who were heads of household suffered as much from combat as the soldiers still living in their father’s households but kept their overall mortality down by dying far less frequently from disease. Soldiers living in a household headed by an unrelated person suffered the highest overall mortality largely because over a quarter of them died in combat.

Some of these outcomes seem explainable. For example, it seems possible that the heads of households suffered less from disease because they were older, had been exposed to more illness, and built immunity over the course of their lives.

I don’t know what accounts for some of the other outcomes. Why, for example, were soldiers living in a household headed by someone unrelated to them almost twice twice as likely as other groups to die from combat?

Conclusion

Even though several types of households predominated among our sample, there was a great diversity of living arrangements. But what strikes me even more forcibly, though, is that every almost man, young or old, belonged to a household of one sort or other—either as a member of at its head. The number of men who lived alone in a boarding house or hotel was negligible.

The other fact that makes a great impression on me is that the young men who still lived with their fathers belonged to households that were wealthier than others. Indeed, their fathers seemed like the type of men who hired men from the other two types of households that predominated among the men who volunteered for the 5th New Hampshire.

Without a doubt, New Hampshire had its rich, middling, and poor people, and in return for a wage, some men worked for others. But it seems possible to exaggerate class differences during this period.

What perhaps mitigated these differences was that many owners of property still worked with their hands. Even though they all owned capital, the farmer on his land, the carpenter in his shop, and the blacksmith at his forge lived by the sweat of their brow. Indeed, most of the men who volunteered for the 5th New Hampshire were unfamiliar with the class relations we associate with modern industrial capitalism. True, by 1861, the factory system had reached New Hampshire, but operatives in the mills of small towns that dotted the countryside still mainly consisted of young women. Moreover, the smattering of iron molders, file cutters, and machinists who joined the 5th New Hampshire were highly skilled craftsmen who probably did not conceive of themselves as forming part of an urban proletariat.

Since these groups differed substantially in a number of ways (e.g. age, wealth, etc.), it should probably come as no surprise that their experiences of the war differed. At this point, though, I’m not prepared to explain exactly how and why. That’s a topic for another post.