Having just finished reading William Child’s Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, I cannot move on without writing a post about his relationship with his wife, Carrie (née Lang).[i] The state of their marriage constituted one of the most important topics they wrote about throughout Child’s military service. While the general outlines of their marital problems are fairly easy to establish from their correspondence, the particulars are not. I have little information about what transpired between them before Child joined the 5th New Hampshire as an assistant surgeon in August 1862.[ii] Moreover, Carrie’s half of the correspondence is no longer extant; the reader must give shape to her grievances by interpreting Child’s responses to her letters. Under these circumstances, rescuing Carrie’s voice is not easy.[iii] Child’s own personality both helps and hinders this operation. As revealed by his letters, Child was sensitive, introspective and, at times, almost neurotic. He tended to mull matters over and worry his problems at length. A naturally anxious person, Child bundled his concerns together which had the effect of compounding his overall apprehension. On the one hand, then, the reader of his letters obtains much detail. On the other, Child’s habit of incessantly reflecting on his difficulties makes one wonder if he made mountains out of molehills.

So what do the letters indicate about their marital troubles?

Starting fairly early in his military service, Child nagged Carrie to write more frequently. It’s not clear how Carrie responded to this hectoring, but since Child complained about this issue to greater or lesser degrees for their entire wartime correspondence, it appears she never met his expectations. Child employed different tactics to extract more missives from her. He pleaded loneliness and homesickness. He told her that he dreamed about her constantly. He complained about how miserable he felt when other husbands in the regiment received letters from their wives and he didn’t. He proclaimed that the women of the North had a duty to support their menfolk. He related stories of war widows who grieved that they no longer had husbands with whom to commune. While we can understand Child’s point of view, he was unfair to his wife. Carrie had to raise several small children (Clinton, born in 1859, and Kate, who arrived in 1861, were eventually joined by Barney in 1863), oversee a household, collect debts owed to Child, fight the town to obtain his bounty money, and perform all manner of miscellaneous tasks—all of which left little time or inclination for writing letters.

William Child (ca. 1862-1864) while he was still an assistant surgeon with the 5th New Hampshire. It’s possible that this picture was taken in October 1863 while he was stationed in Concord, NH. (See Child, Letters from Civil War Surgeon, 165).

It was not just the infrequency of Carrie’s letters but their tone and content that concerned Child. He wished she would drop her “reserve” and freely share her thoughts.[iv] What really seemed to distress him was that although he wrote that he loved her, she never responded as he would have liked to these declarations. Indeed, it appears, she ignored them altogether in her replies.

In a variety of ways, Child sought to elicit some sign of Carrie’s love. He wrote about how much pleasure he derived from the memory of falling in love with her. He described how her love could make him a better man. He even cited a long passage about love in Thomas Thackeray’s The Virginians (which he read during the Gettysburg campaign), and asked her if she agreed that the English author knew something of human nature. The key passage he quoted was as follows:

Canst thou O friendly reader count upon the fidelity of an artless and tender heart—and reckon among the blessings heaven hath bestowed on thee, the love of faithful woman, purify thine own heart and try to make it worth hers. On thy knees, on thy knees give thanks for the blessing awarded to thee. All the prizes of life are nothing compared to that one.[v]

In his darker moments, his letters became more direct; he wondered if she really loved him since she never said so.

By resorting to a variety of techniques to get Carrie to open up, Child showed himself a subtle and practiced correspondent. But despite his cajoling, it was not until the end of 1863 that Carrie began to reveal the sources of her discontent. One obtains the impression from Child’s letters that Carrie’s grievances trickled out only slowly in their correspondence. Either she was reluctant to remonstrate with him or felt it would do little good.

Explicit references to the troubled state of the Childs’s relationship were strewn across many letters spanning about a year (December 1863 to December 1864). For the sake of concision, I will condense their points. While doing so distorts the character of the correspondence by giving their arguments a cohesion that they did not always possess, it also provides greater clarity.

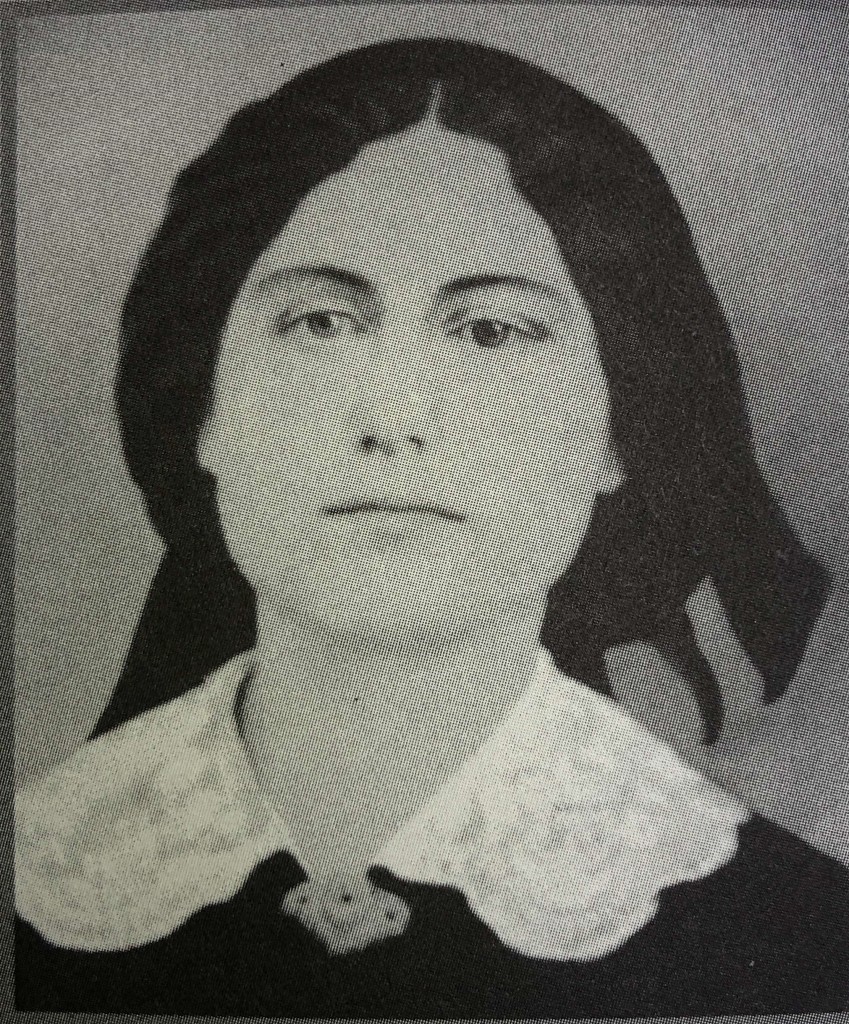

This image of Carrie Child may have been captured in the late summer of 1862 (see Child, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 31.).

Carrie was clearly very unhappy. At one point, she asked if Child had regretted marrying her.[vi] Before the war, she charged, he had been inattentive, and they had done little together. She appeared to believe that their marriage had never been characterized by true love. Indeed, she wrote that he had not loved her as she wished to be loved, and she questioned the purity of his love. One interesting charge she brought against him was that his letters were sometimes “sarcastic.”[vii] It is hard to find much sarcasm in in what Child wrote, but perhaps that’s because our own ironic age is less sensitive to this mode of expression. Or maybe, in her subtle way, Carrie sought to point out the discrepancy between the honeyed words in her husband’s letters and his pre-war treatment of her.

Carrie’s statements must have wounded Child deeply. The surgeon was acutely conscious that he was no lady’s man. Keenly aware that he was not handsome, he wrote that he looked “like an honest big faced New England farmer.” What’s more, despite his skills as a correspondent, he felt he was strange, graceless and without charm.[viii] The way in which Child responded to Carrie’s accusations goes some way toward contextualizing and illuminating them. He continued to insist, of course, that he loved and had always loved her. He pointed out that before the war he had not spent as much time with her as he would have liked because he had needed several years of hard work to establish his medical practice. He also contended that the two of them had much to be grateful for, and he refused to believe that they had not been happy together. Perhaps most interesting, though, he met her charges by recognizing his flaws. He referred to his “peculiar temperament,” “peevishness,” and “hasty temper” that had lost him friends in the past. He admitted that he was “too original, odd [and] unreasonable.”[ix] But he also revealed “that I have the most violent passions to contend with—and the strongest appetites to control.”[x] Child’s references to his “passions,” his insistence that his love was not impure, and his repeated declarations that he would strive for purity in the future all point in a similar direction. The clincher, however, is a passage that appears in a letter he wrote in November 1864:

I love—love you. I can not express the strong, intense feeling—passionate love I have for you. You often ask if my love is that pure love which your heart so much desires,–and which you once said you had not found. O my wife why have you ever doubted that I did not love you as you desire. What can I say or do to convince you. To suppose that I have not the common passions of all men would be to expect from your husband what most wives do not expect from their husbands. . . . But yet with all this there is a feeling within me of a higher and purer nature—the feeling that first came over me so suddenly and strongly If man ever had a pure love for woman such then was my feeling to-ward you.

In other words, it seems to be the case that Carrie believed she was unloved because she felt her husband only wanted sex from her. Since they had never confided in one another on this topic, Child argued, there had been a fundamental misunderstanding. He sought to convince his wife that he desired her physically (because all men had such needs) and loved her.

The correspondence seems to have reached a critical point at the end of 1864. Carrie apparently wrote something that staggered Child. His response testifies to his skills as a writer and serves as a good example of his prose. A letter like this one makes it extremely difficult to doubt his sincerity:

Camp near Petersburg, Va., Dec. 28th, 1864

My Dear Wife:

It has been nearly two weeks since I have received a letter from you but I suppose you have so much time occupied by the care of our babies that you can not write just when you wish. We are now fairly in our winter quarters I think. The time passes very slowly and tediously. Only about an hour is occupied with the sick. So you see we have a long time to read write and sleep. Now and then I become very uneasy and nervous just because I have nothing to do.

Carrie, I can not forget that sentence in your last letter. I have had continually in mind our first acquaintance and life since. I have attempted to ascertain the real and true condition of your own and my heart during all this time. I think we have both been wrong. I have been too carless of your feelings—and you have not been free to communicate to me what was in your heart. But I can not believe but that we have truly loved each other. Yet we each have feared that we were not loved by the other as we wished to be loved. I have had terrible days and nights of doubt. You never caressed—never kissed me of your own account—and I felt that I was not the person who could command all your love for I was neither a hero or a genius—nor perfect. How would come the awful idea that perhaps you might love some man not your husband I can never tell you the perfect agony I have endured. But now I believe I will not believe otherwise—that I have been and am now the person you love, though I do not believe that you have in me your once ideal of what you would have for your husband. One thing is very certain if either of us have the least suspicion that we are not loved—really and truly loved then indeed our domestic happiness is on the very brink of ruin.

It does seem to me that you would not have become my wife had you not loved me. I can not think of the least circumstance that could have influenced you do to so. I am certain that none of our friends were over anxious that we should be married—and neither of us would believe that you could not resist my “blandishments” and “taking arts” [talking arts?]—or that you were deceived. I have not shrewdness to conceal or art to deceive. No, Carrie, nothing except your own lips would convince me that you did not once love me—really love me as my most romantic desire would have it. It may be that you thought you had been deceived in respect to the love I had for you but you were not if I know my own heart.

And although you once told me you did not love me as expected to love your husband yet I hope, believe I shall yet hear you say that you do love me just as you expected to love your husband. While I do hear that word and know that you feel it I shall not have all the happiness I expected in my life of love and marriage. Carrie, I beg, entreat you to freely tell me all your heart—have confidence in me. Distrust excites distrust. Coolness begets coolness. Confidence begets confidence and with it will come love if ever. Carrie, these two years were unpleasant unhappy to us both just because there was not a full, free, confidential understanding between us. But can we say—dare we acknowledge to ourselves that we did not love each other? Can we believe that our children were not begotten in love. The very thought is cruel and unnatural. I suppose neither of us found just what we expected in marriage—or rather we found many unexpected things. But this has been true from Adam and Eve until now—and ever will be so.

Now and hence forward we will not doubt each other’s love. Each shall know the heart of the other. No matter what may appear to be we will only wish to know what is. We shall know and be convinced that love is not a mere romantic idea gone when real life comes, but an existence of two souls in sympathy, bound not merely by law, but by an inexplainable, delicious, lasting affinity which will exist beyond this life. Troubles anxiety trials struggles will come to us as to all others, but we will never cease to love each the other—to make our hearts one. Then there will be a joy a happiness for us both which no person or circumstances can deprive us even though life itself be taken. I will live for you—I will try to be worthy of your love, I desire to be –and if I am not it is because I am naturally weak. I know I am not all that you may wish your ideal husband to be, but in heart I wish to be. It may be that I have had as high aspiration for the good and pure as you, but you must remember that I have been more in the world than you—and have not attained to all I have aspired. But God will judge our hearts—and where I have been weak he will judge lightly—where I have sinned he will—as I hope you will—forgive.

Carrie I must say good-night. My Darling Wife I love, love you. God bless you is ever my sincere, heartfelt prayer. Good night. Kisses to you and the babes. Good night. Good night.

W.[xi]

It remains unclear to what degree this letter alleviated matters between Child and his wife. Unbeknownst to both of them, their wartime correspondence was drawing to a close. The war in the east had a little over three months left to run, and in March 1865, Child obtained a furlough to visit his family (meaning he missed the Appomattox campaign and Lee’s surrender in on April 9, 1865). Child rejoined the 5th New Hampshire in late April and was mustered out in late June. Among the few letters from 1865 that passed between Child and Carrie, one sees little evidence of the crisis that loomed so large during the previous year. I’d like to think that their relationship was on the mend. . . . And yet, in February 1865, Child wrote to Carrie asking for more details of her visit to her mother’s. Child complained,

I can get but little idea of what you are doing or how you are feeling from anything you write. Sometimes I can hardly understand why it is so. I make up my mind not [to] be troubled about it. . . . I know you must have thought and feelings of some kind—either good or bad—pleasant or unpleasant—happy or unhappy. But it is all unknown to me—and I have fully concluded that I never can or shall know your mind exactly. You sometimes bewilder me. Then again I am certain that you love me but I won’t write another word of this—It makes me unhappy to write and you unhappy to read it. You will, I know, write to me more often—and longer letters.[xii]

Perhaps instead of resolving their differences, Child and Carrie had come to accept them. Maybe Carrie, who was not as neurotic as her husband, did not feel compelled to spill all her thoughts across the page. It might have been the case that she sought to keep a part of herself free and independent from her ever-inquisitive husband. In so doing, of course, she kept herself free and independent of historians who now experience that much more trouble in rescuing her voice.

Many readers will find the epilogue to this tale unsatisfying. Once the war ended, William and Carrie Child did not have long together. On May 10, 1867, less than two years after her husband had returned from the war, Carrie died of apoplexy.[xiii] She was only 33. Just over a year later, on September 3, 1868, Child married Carrie’s younger sister, Luvia.[xiv]

[i] William Child, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon (Solon, ME: Polar Bear & Co., 2001).

[ii] All I know is that they appear to have been married in 1854 and that he attended Dartmouth College between that year and 1857 to obtain his medical degree. See https://www.familysearch.org/tree/pedigree/landscape/MMW4-WR8

[iii] I am here reminded of Jill Lepore’s article on microhistory that my colleague, Matt Masur, and I use in History 112: History’s Mysteries. Lepore argues that where “biographers generally worry about becoming too intimate with their subjects and later betraying them,” “microhistorians, typically denied any such intimacy, tend to betray people who have left abundant records in order to resurrect those who did not.” See Jill Lepore, Historians Who Love Too Much: Reflections on Microhistory and Biography” Journal of American History 88: 1 (June 2001): 141.

[iv] Child, Letters, 123.

[v] Ibid., 133.

[vi] Ibid., 225.

[vii] Ibid., 214.

[viii] Ibid., 359.

[ix] Ibid., 314.

[x] Ibid., 313.

[xi] Ibid., 309-311.

[xii] Ibid., 327-329.

[xiii] “New Hampshire Death Records, 1654-1947,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FSKN-R8F : 22 February 2021), Caroline Child, 10 May 1867; citing Bath, Bureau Vital Records and Health Statistics, Concord; FHL microfilm 1,001,067.

[xiv] “New Hampshire Marriage Records, 1637-1947,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FLFR-WLV : 22 February 2021), William Child and Luvia Lang, 03 Sep 1868; citing Bath, Grafton, New Hampshire, Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics, Concord; FHL microfilm 1,000,975.