“The Civil War in America: Claiming Exemption from the Draft in New York,” Illustrated London News (1863): After the draft lottery, enrollment boards had to deal with huge crowds of draftees who needed to undergo a physical examination and whose claims to exemption had to be checked. Moreover, large numbers of substitutes had to undergo a physical as well.

Introduction

I recently read the two most important works on the Northern draft during the Civil War: Eugene C. Murdock’s One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North (1971) and James W. Geary’s We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (1991). These books taught me a great deal about the forces that shaped the Enrollment Act of 1863 (and subsequent amendatory legislation) as well as how the machinery of conscription was supposed to work. At some point, I will attempt to trace how substitutes and draftees were processed by this machinery in New Hampshire, but that will have to await a trip to the National Archives in Boston (which is actually in Waltham—how does that work?). For now, I thought it would make sense to look into the lives of the men responsible for overseeing conscription in the Granite State. Who served on New Hampshire’s draft boards (more properly referred to as “enrollment boards”) during the conflict? By looking at this question, I hope to figure two things out. First, I want to understand the spirit in which the draft was carried out. Second, I hope to chart the personal relationships in New Hampshire that influenced the war effort in this state.

Geary and especially Murdock express much sympathy for those who served on enrollment boards. Murdock represents them as “good, responsible, public servants,” but scholars have not always looked at matters in this light. Geary points out that historians have variously described members of these boards as “insensitive, corrupt, and inefficient” as well as “political hacks” consisting of “Republican favorites and narrow-minded partisans totally lacking tack or judgment.”[i] Were the inadequacies of the Enrollment Act compounded by shabby, mean-spirited execution? Perhaps there is no better way of getting to the bottom of this question than investigating the backgrounds of the men responsible for supervising conscription.

I won’t claim the following is “groundbreaking” research. But I do know that nobody has ever looked at the men who served on New Hampshire’s enrollment boards.

Enrollment Boards

Before diving into the heart of the question, it makes sense to describe who did what on the enrollment board. Each congressional district obtained such a board consisting of three members: a district provost marshal (who held the rank of captain), a commissioner, and a surgeon. The district provost marshal carried the heaviest load. According to regulations:

he was required to preside over the enrollment board, enforce its orders, and keep a record of its proceedings; conduct the enrollment of all able-bodied males between twenty and forty-five, and prepare consolidated lists of such persons; conduct the draft, and notify draftees of their selection; muster draftees, substitutes, and volunteers into service; provide for the housing, feeding, clothing, and transporting to the general rendezvous of all draftees, substitutes, and volunteers; search out and arrest all deserters in the district and ship them to the nearest military post; arrest and deliver to civil authorities all who might resist or counsel resistance to the draft; and keep complete records, financial and otherwise, of all business transacted.[ii]

Each district was divided into subdistricts whose boundaries typically coincided with those of towns (in larger settlements, they accorded with the borders of wards). Every subdistrict had an enrolling officer who registered the men between the ages of 20 and 45 living in his territory (a very difficult job when many people sought to evade the draft and American society was highly mobile). A list of these men generated in each subdistrict was consolidated into a district-wide enrollment list. While the district provost marshal was ultimately responsible for keeping the enrollment list current, it was usually the commissioner who oversaw this task directly.

Every time the president called for troops—and he did so on four occasions while the Enrollment Act was in effect (summer 1863, spring 1864, fall 1864, and spring 1865)—the district provost marshal announced the manpower quota each district had to meet. This quota was based on the size of the enrollment list. If the district and the subdistricts met their quotas through volunteers, all well and good. If they fell short, a draft was required to make up the difference. The regulations foresaw that many drafted men would obtain exemptions so, initially, 50% more men were drafted by lot from the enrollment list than what was required. Since the number of exemptions proved much higher than anticipated, starting in June 1864, twice as many men as necessary were drafted. After the lottery, the district provost marshal, often accompanied by the commissioner, heard the cases made by draftees for exemption.[iii] At the same time, draftees so inclined presented a receipt for the $300 in commutation money they had already paid to the Internal Revenue office (the ancestor of today’s IRS) or a substitute. By this point, the surgeon had already started giving all draftees, substitutes, and volunteers a physical. The size of this task was gargantuan; over the course of the war each enrollment board did just under 10,000 physical examinations. Although they had assistants, conscientious surgeons insisted on doing most of their own exams and attending the ones they did not perform themselves. Once the results of examinations and exemption cases were determined, the district provost marshal held onto the draftees, substitutes, and volunteers until it was time to ship them off under guard to the draft rendezvous (in New Hampshire, this rendezvous was a large stockade located in what was then the southern part of downtown Concord). There, they were eventually distributed randomly to various Granite State regiments like the 5th New Hampshire.[iv]

New Hampshire’s House Delegation after the March 1863 Elections: From left to right: Daniel Marcy (1st District, Democrat); Edward H. Rollins (2nd District, Republican); and James W. Patterson (3rd District, Republican).

Districts and Personnel

I’m afraid the following section will consists of lists that are nonetheless important for understanding the rest of the post.

In 1863, New Hampshire had three congressional districts. There was no question of gerrymandering here because all three grouped together entire counties in a commonsensical way. The first district included the four southeastern counties of Rockingham, Strafford, Belknap, and Carroll. The second district consisted of the two populous and industrial south-central counties of Merrimack and Hillsborough. The third district comprised the four western counties that sat alongside the Connecticut River (Cheshire, Sullivan, Grafton, and Coos). Each of the three districts possessed a population of just over 100,000 people.

| FIRST DISTRICT (Rockingham, Strafford, Belknap, and Carroll Counties) |

| Congressmen Gilman Marston (March 1859-March 1863) Republican from Exeter, NH Daniel Marcy (March 1863-March 1865) Democrat from Portsmouth, NH Gilman Marston (March 1865-March 1867) |

| Enrollment Board (headquartered in Portsmouth, NH) John F. Godfrey, Provost Marshal, appointed April 30, 1863, relieved by special order, Adjutant-General’s Office, December 18, 1863 Nathaniel Wiggin, Provost Marshal, appointed December 29, 1863, resigned July 23, 1864 Daniel Hall, Provost Marshal, appointed July 30, 1864, honorably discharged October 10, 1865 Jeremiah C. Tilton, Commissioner, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged, May 8, 1865 Jeremiah F. Hall, Surgeon, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged June 15, 1865 |

| SECOND DISTRICT (Merrimack and Hillsborough Counties) |

| Congressman Edward H. Rollins (March 1861-March 1867) Republican from Concord, NH |

| Enrollment Board (headquartered in Concord, NH) Anthony Colby, Provost Marshal, appointed April 30 1863, resigned June 16, 1864 Hosea Eaton, Provost Marshal, appointed July 1, 1864, honorably discharged September 30, 1865 Henry F. Richmond, Commissioner, appointed April 30, 1863, appointment revoked November 21, 1863. Samuel Upton, Commissioner, appointed November 25, 1863, honorably discharged May 8, 1865. R. B. Carswell Surgeon, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged June 15, 1865 |

| THIRD DISTRICT (Cheshire, Sullivan, Grafton, and Coos Counties) |

| Congressmen Thomas M. Edwards (March 1859-March 1863) Republican from Keene, NH James W. Patterson (March 1863-March 1867) Republican from Hanover, NH |

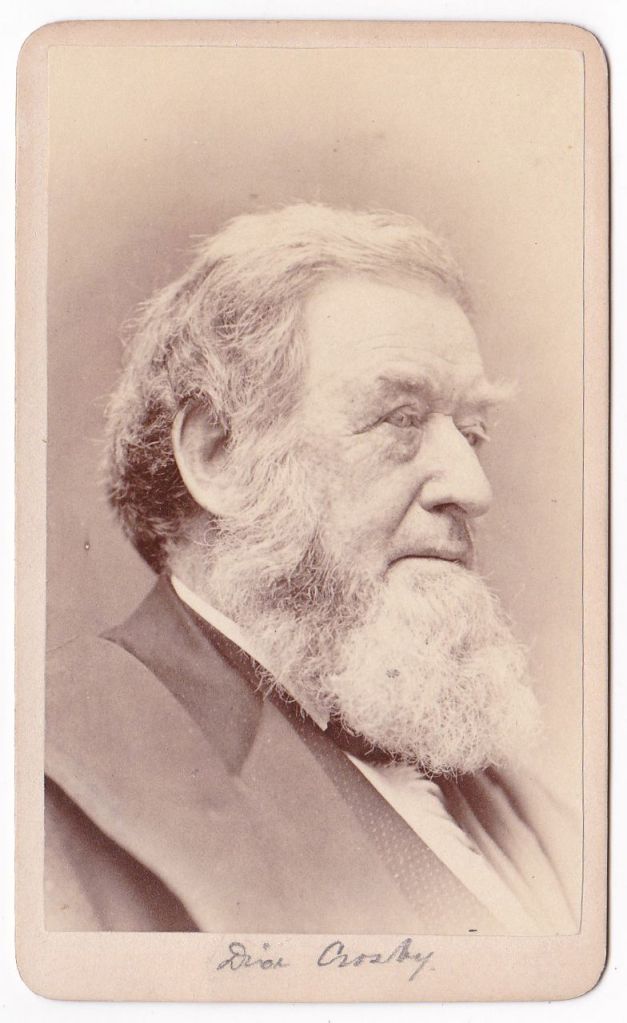

| Enrollment Board (headquartered in West Lebanon, NH) Chester Pike, Provost Marshal, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged, October 10, 1865 Francis A. Faulkner, Commissioner, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged, May 8, 1865 Dixi Crosby, Surgeon, appointed April 30, 1863, honorably discharged June 15, 1865 |

Because it will play some role in our story, it bears mentioning that the two senators for New Hampshire during the Civil War were John P. Hale (July 1855-March 1865), Republican from Dover, NH and Daniel Clark (June 1857-July 1866), Republican from Manchester, NH.[v]

New Hampshire’s Delegation to the Senate in 1863: From left to right: Daniel Clark and John P. Hale.

Appointments

Provost Marshal General James B. Fry appointed members of the enrollment board based on recommendations from the congressmen and leading citizens of the district (no small task since the loyal states had 185 congressional districts).[vi] Positions on enrollment boards, then, resembled patronage jobs—except the pay was much worse. One thing we can say for sure is that since Daniel Marcy, like many Democrats, was an out-and-out opponent of the draft, he was probably not consulted.[vii]

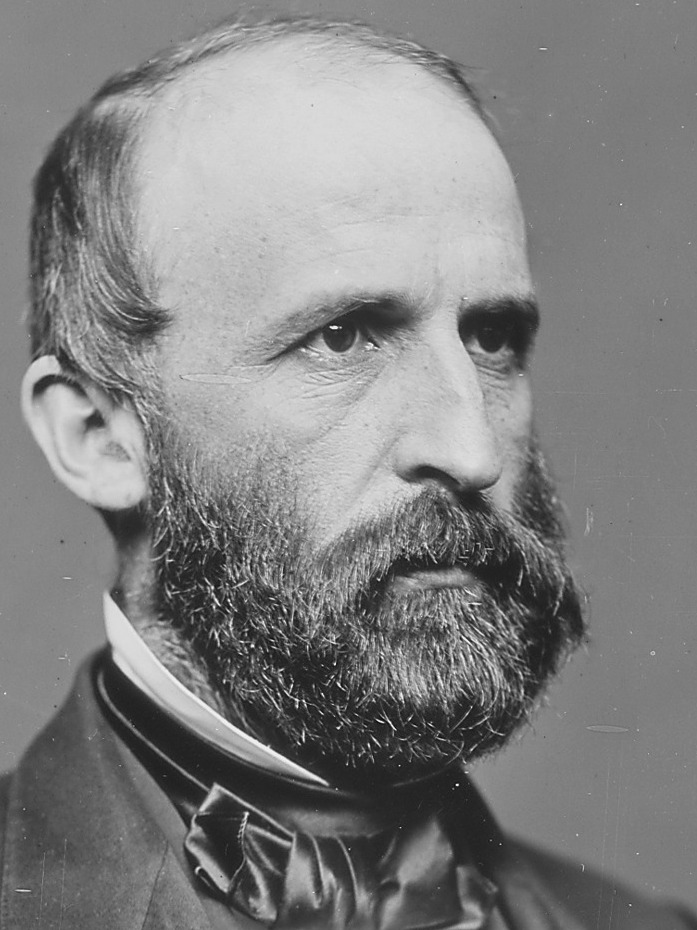

Anthony Colby (1792-1873)

The reason for some appointments is obvious. For instance, Anthony Colby (Provost Marshal, 2nd District) was a former Whig governor and conservative Republican stalwart with extensive militia experience who had overseen New Hampshire’s military mobilization as state adjutant general between 1861 and 1863. He was a natural for provost marshal. To name another example, Daniel Hall (Provost Marshal, 1st District) clearly obtained his position through the good offices of Senator John P. Hale. Hall read law in Dover (where Hale practiced) and was admitted to the bar there in 1860. In the fall of 1861, Hall was appointed secretary of the special US Senate committee that investigated the surrender of the Norfolk Navy Yard. Hale chaired this committee that also included Andrew Johnson (Tennessee), and James W. Grimes (a senator from Iowa born in Deering, NH, who, like Hall, had attended Dartmouth). Shortly thereafter, Hall was appointed clerk to the Senate Naval Affairs Committee which Hale also chaired. Hall went off to war in early 1862, serving on both Amiel W. Whipple (3rd Division, III Corps) and O. O. Howard’s staffs (XI Corps) before ill-health brought him back to New Hampshire in November 1863. Apparently, Hale found Hall a position on an enrollment board that would provide an outlet for his patriotism without taxing his health too much.

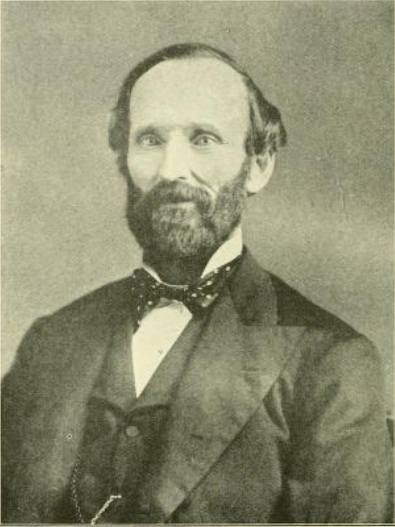

In other cases, we can detect connections that possibly explain a variety of appointments. Samuel Upton (Commissioner, 2nd District) had read law in Senator Daniel Clark’s Manchester office back in the mid-1850s. Nathaniel Wiggin’s (Provost Marshal, 1st District) qualifications for appointment as a district provost marshal were minimal, until one sees that the Wiggin family dominated Stratham, NH, where Clark was born—to a mother who was a Wiggin. Or, to use another example, Francis Faulkner (Commissioner, 3rd District) probably knew Representative Thomas M. Edwards since both had been born in Keene, NH, and practiced law there. Dixi Crosby (Surgeon, 3rd District) was widely known throughout the state as a capable surgeon, but it seems likely that he ended up on the enrollment board because he was acquainted with James W. Patterson, the congressman representing New Hampshire’s 3rd District, a fellow professor at Dartmouth who taught mathematics and astronomy.

Samuel Upton (1824-1902)

In some instances, at this great remove in time and with the sources available to me, the reasons for several appointments are utterly obscure. Indeed, Henry Richmond (Commissioner, 2nd District), a civil engineer who spent most of his life in Nashua, himself was obscure. He appears to have left no trace in New Hampshire aside from census records. And then there’s the case of John F. Godfrey (Provost Marshal, 1st District), a colorful character. Son of a prominent Bangor, ME, lawyer, Godfrey ran away to sea at the age of 15, only returning home when the war broke out. He served as a lieutenant with the 1st Maine Light Artillery and as a captain in a locally raised company of the 1st Louisiana Cavalry (US) before his appointment to the enrollment board. A survey of his military service shows no New Hampshire connections (although the First District was the one closest to Maine).

John F. Godfrey (1838-1885)

Turnover

In his report after the war, Provost Marshal General Fry referred to the “sizable turnover in personnel” on enrollment boards and in the same breath claimed they experienced a “fair degree of stability.”[viii] We see both in New Hampshire. The First District experienced some difficulty in finding a suitable provost marshal while the Second District saw turnover in the provost marshal and commissioner positions. In the Third District, however, the same personnel served throughout the enrollment board’s existence.

We can speculate as to why some men gave up their positions on the enrollment board—or were compelled to do so. Richmond (Commissioner, 2nd District) had his appointment revoked right after the first draft lottery was completed which suggests he was guilty of some shortcoming in its conduct. Godfrey (Provost Marshal, 1st District) appears to have left of his own volition because he managed to secure a lieutenant colonelcy in the 2nd Maine Cavalry in the Department of the Gulf (XIX Corps). It’s possible that regulations, enrollment lists, and such were not to Godfrey’s liking. Fighting and adventure were more his line. (After the war, he participated in an army expedition against the Sioux in Montana and later moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1870s where he became city attorney.) [ix] Wiggin (Provost Marshal, 1st District), who replaced Godfrey, only lasted for one draft which indicates he was not up to the job. We can probably attribute Colby’s resignation (Provost Marshal, 2nd District) to exhaustion due to old age (he was 71). Much of this, though, is speculation.

Occupations and Service

Murdock thoughtfully observes that

A draft board was a totally novel institution in American life. No one could be expected to know either how it would function or what type of qualifications would suit a man for service on such a board. . . . Appointments were made for political reasons in most cases, but some account was also taken of business talent and general standing in the community. However, since the need for speed in setting the draft machinery into operation was so great in the spring of 1863, not every man’s credentials could be fully checked. Many of the appointees, it turned out, simply lacked the ability to do the job.[x]

Murdock is correct, but after the fact, we can see clearly which qualifications and talents fitted a man for service on an enrollment board (aside from the surgeons whom we’ll discuss later). Successful members of an enrollment board tended to possess a head for business, a capacity to understand regulations (and how to apply them), a measure of social intelligence, a fair amount of shrewdness, and, at times, some physical courage.

Jeremiah C. Tilton (1818-1872)

Not surprisingly, then, those who served out their terms on enrollment boards tended to be extremely active men of many parts. For example, while Anthony Colby (Provost Marshal, 2nd District) was always listed in the census as a farmer, he had built a grist mill and proved instrumental in starting stage line between Lowell, MA, to Hanover, NH. He also made a substantial investment in a large New London scythe manufacturing firm—Phillips, Messer, & Colby Company. To this he added his experiences as a politician, an administrator, a militia officer, and a social reformer with a special interest in temperance and education.[xi] Or take Jeremiah Tilton (Commissioner, 2nd District). Aside from running a small factory (J. & J. C. Tilton) that manufactured woolens or hosiery (accounts differ) in Northfield, NH, he attained high rank in the state militia and was involved in local politics during the antebellum era. That he served as a captain of the commissary of subsistence for part of the war (some of that time being spent with General Darius Couch’s 1st division, VI Corps during the Peninsula campaign) speaks, perhaps, to his administrative acumen.[xii] Chester Pike (Provost Marshal, 3rd District) is yet another example of someone who had his finger in many pies. Inheriting a horse-breeding and –trading business in Cornish, NH, from his father, Pike became a farmer on a very large scale who developed substantial interests in the wool business. A partner in Dudley & Pike, which sold meat and dairy products to Boston, Pike was one of those capitalists who took full advantage of the new market economy emerging in northern New England at the time. Not surprisingly, Pike became an enthusiastic booster of farming in New Hampshire, serving as the President of the Connecticut River Agricultural Society for a number of years. What’s more, he made a substantial investment in his community as a selectman, county commissioner, state legislator, town moderator, and school board member in a political career that stretched all the way into the late 1890s.[xiii]

Chester Pike (1829-1897)

It is also striking—but perhaps entirely predictable—that a number of those who served out their terms on the enrollment board were attorneys. Daniel Hall (Provost Marshal, 1st District), Samuel Upton (Commissioner, 2nd District), and Francis Faulkner (Commissioner, 3rd District) all were—or soon became—lawyers of some note. And like Colby, Tilton, and Pike, they, too, were “joiners” deeply invested in civic life on a state and national scale. After the war, Hall became a pillar of the Dover bar, the Republican Party, and the Grand Army of the Republic. Among other commitments, he served as a trustee and secretary of the Soldier’s Home in Tilton, NH, a trustee of Berwick Academy, and a member and president of the New Hampshire Historical Society.[xiv] Upton was the justice of the police court in Manchester from 1857 to 1874 (at which point he moved to Iowa), became a Republican Party stalwart, assumed a large role in the New Hampshire temperance movement, and, as an enthusiastic Congregationalist, threw his support behind the erection of Sunday schools.[xv] Although Faulkner was a busy and formidable lawyer, he also served as county solicitor, town moderator, and representative to the state legislature. Like Hall and Upton, he was a very active Republican (one of his biographers claimed Faulkner “was deeply interested in political affairs, and no man in his section wielded more influence”). He was later appointed justice of the state supreme court in 1874 (he declined to serve) and became a member of the state constitutional convention in 1876. Faulkner was also something of a man of business; he found time to act as a director of the Ashuelot and Cheshire National Banks, and at the time of his death, he had become president of the Cheshire Provident Institution for Savings.[xvi]

And, lest we forget, three of those who served on New Hampshire’s enrollment boards had seen army service during the war: Godfrey (Provost Marshal, 1st District), Tilton (Commissioner, 2nd District), and Hall (Provost Marshal, 1st District).

It is in this context of extensive commitments to business and public service that one must view these men’s membership on enrollment boards.

Surgeons

The qualities demanded of a surgeon on an enrollment board were somewhat different; surgeons brought to the board professional knowledge that could only be obtained through a specialized education and long experience. It is significant that in all three districts the surgeon initially selected to serve on the enrollment board remained until the end of the war. That either suggests surgeons were very well equipped for the tasks associated with this service—or that there was enormous difficulty in finding surgeons willing to serve. Or both.

Of the three, Robert Carswell (Surgeon, 2nd District) was the least prominent. For one thing, unlike the other two, he had not gone to Dartmouth (instead attending the less prestigious Worcester Medical School which closed in 1859). Moreover, having attended medical school in his early 30s, he was a late bloomer. Although one biography claims Carswell “met with excellent success as a physician” in Weare, NH, the Census of 1860 indicates his total estate was worth $2800—far less than what Hall and Crosby had amassed. His practice did not take off until he moved to Salisbury, MA after the war. There is some evidence that he may have used opportunities presented by the war to drum up business. In 1862, he became an examining surgeon for army recruits in central and western Hillsborough County. The next year, he received an appointment as an examining surgeon for the pension department. Even so, Carswell, in his limited way, was also a “joiner.” He was elected several times to the state legislature and for many years served as a justice of the peace in Weare.[xvii]

Jeremiah Hall (1816-1888)

Jeremiah F. Hall (Surgeon, 1st District) fits the profile of those men who engaged in a great variety of activities. Although he was active in the medical community (he belonged to the New Hampshire State Medical Society, the Carroll County Medical Society, and the Strafford County Medical Society), he also dabbled in politics (state senate and Portsmouth alderman), business (director of the Lake National Bank of Wolfeborough, trustee of the Five Cent Savings Bank, and eventual president of the Portsmouth Trust and Guarantee Company), and what we would call today the non-profit sector (trustee of Wolfeborough Academy and the New Hampshire Asylum for the Insane). In whatever spare time he possessed, Hall also wrote several medical papers, including one enitled “Hay Fever” (from which he suffered), and occasionally cranked out a poem or two (which he sometimes read at the meetings of the medical societies to which he belonged).[xviii]

I’ve already written a fair bit elsewhere about Dixi Crosby (Surgeon, 3rd District), so I won’t go into extensive detail about his work. It suffices to say that while he was a temperance man who briefly served in the state legislature, his life revolved around his professional interests. He taught at Dartmouth for decades and mentored an entire generation of surgeons and physicians in the state. In his prime, he was widely considered one of the best surgeons in New Hampshire, and he enjoyed a thriving practice. He was also a central figure in the New Hampshire Medical Society.

The surgeons’ reports that appear in Statistics Medical and Anthropological of the Provost-Marshal-General’s Bureau (1875) reveal as much about the men themselves as they do about their work. Yes, they are characterized by various idiosyncrasies. Crosby was very much disturbed by the frequency of first-cousin marriage in parts of his district, and Hall excoriated the “fearfully prevalent habit of masturbation” which he believed was “a common cause of feebleness in many young men.” But in their similarities, these reports show that all three men belonged to the same professional tribe that took its tasks seriously. All describe the difficulties faced by surgeons in dealing with shamming among draftees (who played up their ailments) and frauds among substitutes (who downplayed their disabilities). Crosby was perhaps the cleverest in detecting attempts to fool him, but none of the others had any illusions about what he was up against. All sought to make the best of a difficult job.[xix]

Wealth and Education

As the foregoing might imply, most of the enrollment board members were well educated. After all, it’s hard to think of anybody who underwent more formal schooling in mid-19th-century America than surgeons and attorneys. The surgeons, of course, had gone to medical school—two of them (Dixi Crosby and Jeremiah Hall) to Dartmouth. Daniel Hall also graduated from Dartmouth. Faulkner went to Phillips Exeter Academy before heading to Harvard. Even those who did not attend college went to excellent schools. Samuel Upton, who came from humble origins, and Chester Pike, who did not, both attended Kimball Union Academy which, then, as now, was considered a path to an elite college.

Daniel Hall (1832-1920)

In this context, it also makes sense to point out that almost all the men who served on New Hampshire’s enrollment boards were either very well off or belonged to families with a great deal of money. Dixi Crosby and Anthony Colby headed the list with estates of around $15,000 (at a time when the median estate in New Hampshire was $1100). Even Hosea Eaton, whom the Census of 1860 identified as a carpenter, possessed property amounting to $2100. Almost everyone else fell somewhere between $3000 and $8000. Jeremiah Tilton, who was nominally the poorest member of any enrollment board (estate of $1600), had nothing to fear. He was both the first cousin and brother-in-law of the fabulously wealthy Charles E. Tilton (of Tilton, NH fame) whose fortune ran into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[xx] Even the mysterious Henry Richmond, who, according to the Census of 1860, had no occupation, lived with his mother who possessed an estate of $10,000. Clearly, the men who served on New Hampshire’s enrollment boards did not do it for the money.[xxi]

Party Affiliation

Of the 13 men who served on New Hampshire’s enrollment boards, I found the party affiliations of seven—all of whom were Republicans. I suspect that if I looked harder, I could find the party affiliations of the remainder, but I suspect almost all of them were in some way associated with the Republican Party. After all, much of the state Democratic Party was hostile to the draft.

The older generation—and here, I think primarily of Anthony Colby (Provost Marshal, 2nd District)—came to the Republicans via the Whigs. There was something old-fashioned about Colby’s attitude toward politics as evidenced by this story regarding Daniel Webster’s efforts to drum up New Hampshire Whig support for the Compromise of 1850:

[Colby’s] party favored the passage of the Fugitive Slave bill, and Daniel Webster, as its advocate, wrote Governor Colby, asking that he would stand by him. Privately, the governor considered the whole business, as he quaintly expressed it, ‘like stuffing a hot potato down a man’s throat and then asking him to sing “Old Hundred,”’ but loyal to his party and life-long friend, he wrote Mr. Webster that although the bill was odious to him personally, he would do all he could; and the time came when he nobly fulfilled his promise.[xxii]

One can view Colby’s attitude as either gentlemanly or repulsive. It is possible this anecdote is apocryphal, but knowing what we know about Webster and Colby, it does sound plausible.[xxiii]

Whatever the case, the younger generation came to their party affiliation through a hard path—or at least that was the way their contemporaries remembered it. For instance, Daniel Hall (Provost Marshal, 1st District) started adulthood as a Democrat, but he began to second-guess his loyalties with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Once he expressed his disgust with the Lecompton Constitution in 1858, he lost his patronage job at the New York Customs House (the intimation being that since the Democrats no longer considered him loyal, they turfed him out of the position). The next year, he declared himself a Republican.[xxiv] Or take the example of Samuel Upton (Commissioner, 2nd District). A contemporary remembered that Upton began his political life as a member of the Liberty Party and an abolitionist when such opinions “even in New England subjected one to vile taunts and social ostracism.”[xxv] Faulkner (Commissioner, 3rd District) was remembered as “a staunch and consistent Republican, and a leader in his party. To his sagacity and firmness, especially during the Rebellion, the party owed much.”[xxvi] This evidence intimates is that the Republicans who came of age a generation after Colby were more militant, principled, and willing to face the slings and arrows of fortune.

Francis Faulkner (1825-1879)

Conclusion

The proof of the pudding is not in its looks but in the eating. Likewise, we should judge these men not by appearances but by what they did while serving on the enrollment boards, and that will require more research in the National Archives, especially in RG 110. At first glance, however, the provost marshals, commissioners, and surgeons who oversaw the draft in New Hampshire make a favorable impression. Several resigned or had their appointments revoked, and there may be stories there that cast a poor light on the boards involved. But it is interesting that the men who left the boards in this way were the least prominent of the group.

A sizable proportion of the enrollment boards consisted of lawyers and physicians. Although several came from humble backgrounds, almost all were wealthy or on their way to becoming so. Not surprisingly, there was a high standard of education among this group.

They generally appeared to be well connected, and in several cases, it must be conceded that they were selected for flimsy reasons. Many were joiners who mixed personal ambition with public service. Because of who they were, it made sense that they were politically active. And circumstances being what they were, if they were politically active, they had to be Republicans.

In other words, they lived a world away from the draftees and substitutes they dealt with since the former were poor, and the latter were poor and foreign-born. And perhaps that meant these enrollment boards were not as empathetic as they could have been in carrying out their duties.

But in imagining the kind of job they might have done, we ought to remember the way their stints on enrollment boards were framed in the various town and county histories that recounted their life stories. Invariably, that service was described as an honorable public trust that was of a piece with their careers in public and private service to the community. These histories tend to be hagiographic, but many members of New Hampshire’s enrollment boards had long habituated themselves to serving their localities. The war provided them with an outlet for their patriotism and a chance to serve their nation according to their lights as Republicans. And that service was carried out with characteristic rectitude, or so the stories go. One account relates that a substitute broker said of Daniel Hall (Provost Marshal, 1st District), “He was one of the men that no man dared approach with a crooked proposition, no matter how much was in it.”[xxvii] The story sounds suspect (where did the author find a substitute broker willing to incriminate himself in such a way?), but also has an air of verisimilitude.

Dixi Crosby (1800-1873)

With the exception of Robert Carswell (Surgeon, 2nd District), no one appeared to have profited (or sought to profit) from this line of work. Indeed, men worth thousands of dollars agreed to serve in a position that paid slightly more than $100 per month. And we cannot forget the service was arduous. In his final report, Crosby stated that although he had examined eighty men in one day, “no surgeon can do himself or the Government justice if he attempts to examine more than fifty men per day.” Indeed, he pointed out that during every examination, he had to go through a number of different motions to make recruits understand exactly what he wanted them to do. With foreign-born substitutes whose command of English was imperfect, the job was doubly difficult: “I am obliged to make my meaning clear by jumping, running, &c., and, as may be well imagined, fifty repetitions of this active course of calisthenics are about as many as can be endured by any man, however vigorous and strong.” At the same time, Crosby mentioned the frequency with which former patients counted on him to exempt them from service. As he put it, “Under the most favorable circumstances, the surgeon cannot avoid giving great offense to many who fancy they have a claim upon him, based on long years of professional patronage. The surgeon must submit to considerable abuse and to receive letters more pointed than polite from those of his neighbors whom his decision has rendered ‘fit food for powder.’”[xxviii] The man writing these words was a 65-year-old physician with an estate of $15,000 and an excellent local reputation. Like the other members of New Hampshire’s enrollment boards, Crosby had everything to lose and nothing to gain from his service—except the sense of having done his duty. Surely this situation must incline us to form a favorable impression of most enrollment board members who served in New Hampshire—until further research indicates otherwise.

[i] James Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1991) 71.

[ii] Eugene C. Murdock, One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971), 92.

[iii] A man could claim exemption if he suffered from a physical or mental disability; if he was a person of foreign birth who had never declared his intention of becoming a naturalized citizen (an “alien” in the parlance of the day); if he was over- or under-age; or if his enlistment would cause financial hardship for his family. A man could only qualify as a substitute if he was ineligible for the draft which meant that a huge proportion of substitutes were foreign-born “aliens.”

[iv] Murdock, 8-11.

[v] Information on who served on which board comes from The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series III, Volume V (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1900), 891

[vi] Murdock, 8.

[vii] William Marvel, “New Hampshire and the Draft, 1863” Historical New Hampshire, 36:1 (Spring 1981), 65.

[viii] Murdock, 93.

[ix] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_F._Godfrey; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8721830/john-franklin-godfrey; https://archivesspace.williams.edu/repositories/4/resources/561

[x] Murdock, 94.

[xi] Duane Hamilton Hurd, History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis & Co., 1885), 434-435; Myra Belle Horne, A History of the Town of New London, Merrimack County, New Hampshire, 1779-1899 (Concord, NH: The Rumford Press, 1899), 228-231.

[xii] Lucy Rogers Hill Cross, History of Northfield, New Hampshire, 1780-1905 (Concord, NH: Rumford Printing Co. 1905), 303-304

[xiii] Biographical Review; Containing Life Sketches of Leading Citizens of Merrimack and Sullivan Counties, N. H. (Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1897), 362-363.

[xiv] John Scales, History of Strafford County, New Hampshire and Representative Citizens (Chicago: Richmond-Arnold, 1914), 634-541; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/153081853/daniel-hall

[xv] D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Hillsborough County, New Hampshire (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis, 1885), 34-35.

[xvi] Simon Goodell Griffin, A History of the Town of Keene from 1732, When the Township was Granted by Massachusetts, to 1874 When It Became a City (Keene, NH: Sentinel Print Col, 1904), 595-596; D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Cheshire and Sullivan Counties, New Hampshire (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis, 1886), 13-15.

[xvii] George Hiram Greeley, Genealogy of the Greely-Greeley Family (Boston: F. Wood, 1905), 480; William Little, The History of Weare, New Hampshire 1735-1888 (Lowell, MA: S. W. Huse & Co.), 757.

[xviii] Granville Priest Conn, History of New Hampshire Surgeons in the War of Rebellion (Concord, NH: Ira C. Evans, Co., 1906), 183-184; Lucy Rogers Hill Cross, History of Northfield, New Hampshire, 1780-1905 (Concord, NH: Rumford Printing Co., 1905), 151-152.

[xix] For excerpts from all three reports, please see Statistics, Medical and Anthropological, of the Provost-Marshal-General’s Bureau (Washington, DC: Govt. Print. Off., 1875), 180-190.

[xx] Jeremiah was Charles’s first cousin, and Charles married Jeremiah’s sister (also Charles’s first cousin) in 1856. That’s how Jeremiah became Charles’s first cousin and brother-in-law. First-cousin marriage (which Dixi Crosby strenuously complained about in his report) was not outlawed in New Hampshire until 1869.

[xxi] I could not locate Colby in the Census of 1860. In the Census of 1850, he is listed as having real estate to the value of $15,000, and in the Census of 1870, he possesses a total estate worth $20,000. “United States Census, 1850”,FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MWZK-9CZ : Tue Oct 03 09:13:56 UTC 2023), Entry for Anthony Colby and Eliza A Colby, 1850. For the others, see: “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MDC7-WJF : Fri Oct 06 11:32:44 UTC 2023), Entry for John E Godfrey and Elizabeth A Godfrey, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WV-DS1 : Thu Oct 05 04:59:43 UTC 2023), Entry for Nathaniel Wiggin and Nancy Wiggin, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WT-KR7 : Fri Oct 06 00:57:46 UTC 2023), Entry for Gilman Hall and Eliza Hall, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WL-Q53 : Thu Oct 05 04:15:31 UTC 2023), Entry for Jeremiah C Tilton and Emily Tilton, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WP-D52 : Wed Oct 04 10:27:23 UTC 2023), Entry for Jeremiah F Hall and Annette A Hall, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7W5-XM9 : Thu Oct 05 09:43:37 UTC 2023), Entry for Hosea Eaton and Mary W Eaton, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WJ-J1R : Wed Oct 04 03:45:40 UTC 2023), Entry for Lucy A Richmond and Henry F Richmond, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WB-3P8 : Fri Oct 06 04:13:47 UTC 2023), Entry for John Craig and Mary Craig, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WP-8G7 : Thu Oct 05 06:31:32 UTC 2023), Entry for Robt B Carswell and Alvan Hamilton, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WG-K72 : Fri Oct 06 16:42:40 UTC 2023), Entry for Chester Pike and Ebenezer Pike, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WB-ZT5 : Tue Oct 03 11:56:01 UTC 2023), Entry for Francis A Faulkner and Caroline H Faulkner, 1860; “United States Census, 1860”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M7WT-Z7T : Fri Oct 06 04:46:22 UTC 2023), Entry for Dixi Crosby and Mary J Crosby, 1860.

[xxii] Myra Bell Horne Lord, A History of the Town of New London, Merrimack County, New Hampshire, 1799-1899 (Concord, NH: The Rumford Press, 1899), 230.

[xxiii] Michael F. Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 639-640.

[xxiv] John Scales, History of Strafford County, New Hampshire and Representative Citizens (Chicago: Richmond-Arnold, 1914), 637

[xxv] The same account recalled, “On the slavery question [Upton] had but one opinion,–that if human slavery was not wrong, nothing was wrong, and he lost no opportunity to wage warfare on the institution.” See D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Hillsborough County, New Hampshire (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis, 1885), 34-35.

[xxvi] Duane Hamilton Hurd, History of Cheshire and Sullivan Counties, New Hampshire (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis. 1886), 14.

[xxvii] John Scales, History of Strafford County and Representative Citizens (Chicago: Richmond-Arnold, 1914), 639.

[xxviii] Statistics, Medical and Anthropological, of the Provost-Marshal-General’s Bureau, 188-189.