Charles McCully’s headstone at Westlawn Cemetery, Goffstown, NH

Shortly after Memorial Day, I walked through Goffstown’s Westlawn Cemetery. The cemetery forms part of a route I take through Goffstown Village that amounts to almost three miles. I noticed that a number of small American flags had been planted throughout the cemetery that strikingly indicated just how many of the dead had served in the armed forces throughout our nation’s history (Westlawn was opened around 1817, so it includes Revolutionary War veterans). While ambling along the main path through the cemetery, I thought I’d visit Joseph Caraway’s tombstone. I wrote a post about Caraway some time ago because I once believed he was the sole member of the 5th New Hampshire who had a Goffstown connection.

I found Caraway’s gravesite without difficult, but there was no flag. It occurred to me that nothing indicated he was a veteran—no inscription on his stone and no GAR marker—so that may have explained the absence of a flag. As I walked about that section of the cemetery, though, I noticed several government-issued headstones for Civil War veterans had no flags either. Among these was a marker for someone who had served in the 3rd New Hampshire and another for a veteran from a Vermont regiment. Between these two stones was an eroded marker that I could read only with difficulty. I don’t know why I tarried to decipher it but, eventually, to my delight, I realized it read:

Charles McCully

Co. G 5 REG. N.H.V.

1834-1903

The name didn’t ring a bell, so I looked him up as soon as I reached home. Sure enough, The Revised Register of the Soldiers and Sailors of New Hampshire in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1866 had a record for “Charles McCulley.”[i]

Tracing this soldier’s story was somewhat difficult since “McCully” was an alternate spelling of “McCullough,” and many people, especially in the New York area, where our man was born, bore that last name. Another issue was that McCully’s life was somewhat checkered, and he sought to keep parts of his past a secret. I’m about 90% sure, though, that the following story is correct; in a number of cases, I’ve found ways in which the various documents I used confirm each other.

Charles McCully was born in New York, NY, in either 1833 or 1834. I could not locate him in the Census of 1850. However, I did find a likely candidate in the Census of 1860, a Charles McCully who was 26 years old, lived in Brooklyn, NY, and worked as a “Carman” (a driver of a horse-drawn delivery vehicle). He appears to have been married to an Ellen McCully, aged 22, but she makes no further appearance in any of the documents I found. McCully also lived with a pair of peddlers, Samuel Lockwood (50) and Charles William (22).[ii] So far, so good; nothing to see here.

Colonel William Wilson (seated, center) poses with two officers and members of his 6th New York. A very interesting biography of Wilson by Robert E. Cray, entitled, A Notable Bully: Colonel Billy Wilson, Masculinity, and the Pursuit of Violence in the Civil War Era appeared in 2021. In a review of this work, Lorien Foot quotes Cray to the effect that Wilson’s story is “worth knowing” if we want to understand the Northern public’s shifting attitudes toward bullying, masculinity, and violence. The problem is that “‘roughs’ did not leave diaries, letters, and papers for historians to examine their personal lives and private opinions.”

Only a couple of weeks after Fort Sumter was attacked, McCully enlisted in the 6th New York Infantry Regiment, otherwise known as “Wilson’s Zouaves” after its colonel, William Wilson. I love the Wikipedia description of the unit: “It was made up primarily of gang members, ex-cons, and criminals from the Bowery section of New York City. Rumor had it that a man had to prove he’d served time in jail before he was allowed to join.” Is this true? I have no idea since no source for this information is provided. But I have read elsewhere that the regiment consisted of “rowdies” and that it was notoriously ill-disciplined. McCully enlisted on April 25, 1861 and was mustered in as a sergeant in Company D five days later. Only two months passed before McCully was busted down to private (on the 4th of July, no less). In August 1862, he was promoted back to corporal, and this was the rank he held when the regiment reached the end of its two-year term.[iii] The 6th New York appears to have done more posturing than fighting (unless one counts the fistfights in which it was involved with nearby Union units). It was initially stationed on Santa Rosa Island near Pensacola, FL, where it engaged in several small skirmishes with Confederate forces. The 6th New York was later transferred to New Orleans, LA, and thence to Baton Rouge. After participating in operations against Port Hudson, it fought some minor actions in western Louisiana before mustering out in New York in June 1863.[iv]

This image from the May 18, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly shows Colonel Wilson and his staff. The accompanying article stated that the 6th New York “has been recruited from the roughs and b’hoys of New York city.”

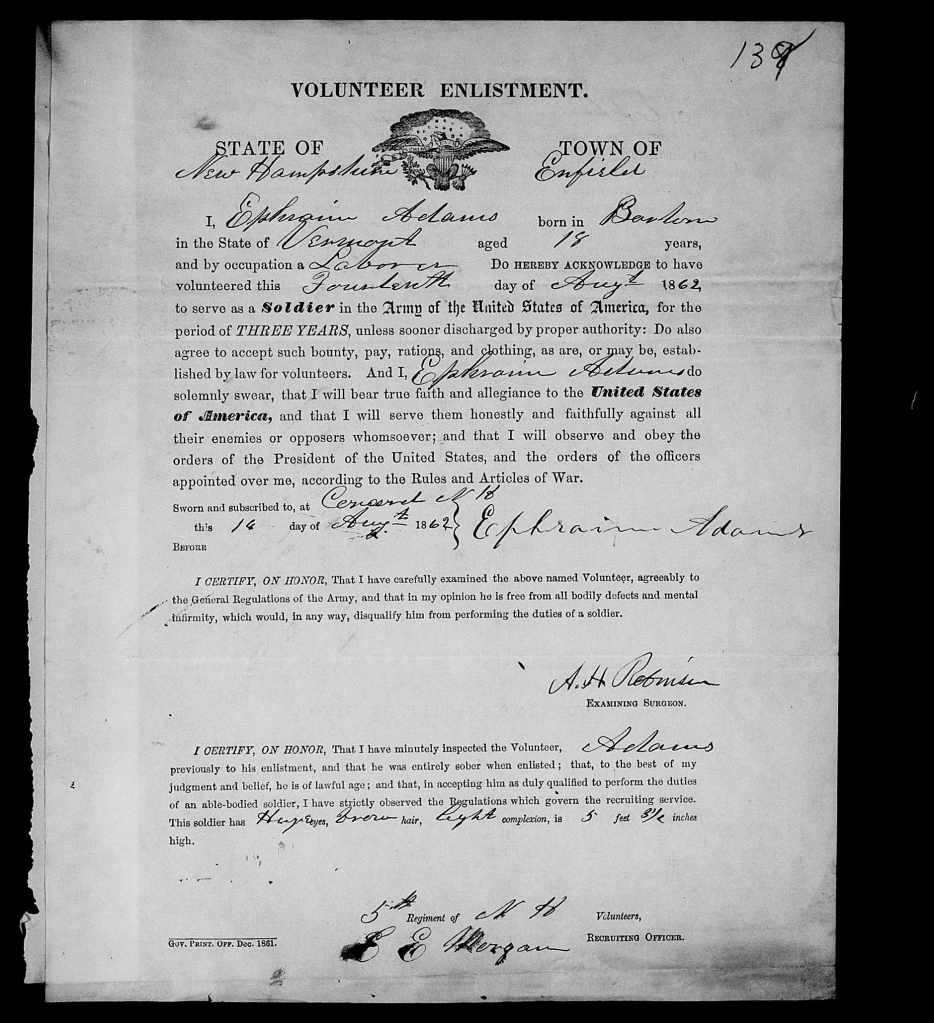

What McCully did for the next five months remains unclear. All I know is that in December 1863, he enlisted in the 5th New Hampshire and was mustered into Company G as a private. According to the muster roll, McCully was a “Drayman” with brown eyes, dark brown hair, and a ruddy complexion.[v] He stood 5’ 8 ¼”. Interestingly, every single man who appeared on the same page as he did was from out of state, and a very large proportion was foreign born.[vi]

It seems odd that a New Yorker would enlist in a Granite state unit, but there are possible explanations. To meet the manpower quotas set by the state, New Hampshire towns sent agents to New York to collect men who were willing to serve as substitutes for sums that in the summer of 1863 often topped $500. It appears these agents may also have collected some men who were attracted by the large bounties offered in New Hampshire for volunteers (towns, the state, and the federal government each contributed to these bounties). It’s possible McCully found these terms enticing. Since the 5th New Hampshire was then at Point Lookout, MD, guarding Confederate POWs, he may also have joined because he thought the regiment would spend much of its time performing cushy service.

The service was cushy. Until it wasn’t. In late May 1864, the regiment left Point Lookout to take its turn in the Overland Campaign. On June 3, 1864, a couple of days after reaching the Army of the Potomac, the 5th New Hampshire was thrown into the grand assault against Confederate forces at Cold Harbor. I’ve written about this battle elsewhere. It suffices to say here that the regiment performed well and was one of only two Union units to break through the front line of the Confederate defenses. Unfortunately, since other regiments did not advance with the same kind of spirit, the 5th New Hampshire’s flanks were uncovered. The rebels shot the regiment to pieces and took 40 men prisoner. Charles McCully was one of those who was wounded. For reasons that will become clear shortly, I have not been able to determine the nature of his wounds.

Alfred Waud, 7th N.Y. Heavy Arty. in Barlows charge nr. Cold Harbor Friday June 3rd, 1864 (1864): The 5th New Hampshire broke into the Confederate defenses at Cold Harbor right next to the 7th New York Heavy Artillery. After experiencing some local success, both regiments were cornered, badly used by rebel forces, and driven off.

McCully was transported to Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC (just like Ephraim Adams). From there, he was sent to a hospital in Philadelphia, PA. And there the record in The Revised Register ends with an ominous “N.f.r.A.G.O.” an abbreviation that signifies “No further record Adjutant General’s Office.” In my experience, this notation indicates a man probably deserted. This surmise is confirmed by a muster roll that notes: “No discharge furnished—Wounded June 3rd 1863—Abs[en]t in U.S. Hosp[ita]l Annapolis MD.”[vii] Desertion from hospitals was common. When some men felt well enough to leave under their own power, they checked themselves out, never to return to the army.

Except McCully did return to the army. In September 1865, he showed up at Fort Hamilton (which now sits under the Brooklyn end of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge) and enlisted in the 2nd battalion of the 12th US Infantry Regiment.[viii] In 1866, this battalion later became the 21st US Infantry Regiment after the army was expanded to assume the arduous responsibilities associated with Reconstruction. For most of the time that he remained with the regular army, McCully was stationed near Richmond, VA. He stayed with the 21st US Infantry until January 1867, when he was discharged at Petersburg, VA, for disability. It may seem odd that a sometime troublemaker and deserter would return to the army, but during the Civil War, some men developed a taste for the life and tried to make a go of it. The 5th New Hampshire had a number of such men.

An image of the shoreline in front of Fort Hamilton at some point in the 1870s.

McCully then disappears from the documentary record for 13 years. Or at least, he seems to have disappeared from FamilySearch. One wonders if, as a deserter from the 5th New Hampshire, he sought to keep a low profile.

McCully next came up for air in Goffstown, NH. The Census of 1880 enumerates a “C. Worley McCully,” aged 45, born in New York, and boarding with the family of Franklin Tucker, a 41-year-old laborer. I have no doubt this is our man. So far as I can see in the Census of 1880, there was no other McCully living in New Hampshire whose first name started with a “C.” Why McCully moved to New Hampshire remains a mystery. One might be tempted to say he knew somebody there from his 5th New Hampshire days. However, nobody from Goffstown enlisted in the regiment during the war, and that meant very few people in town had any connection to the unit. (Franklin Tucker had spent most of the war with the 2nd New Hampshire and was also wounded at Cold Harbor, but there is no evidence that he knew McCully during the war.) If only we knew what McCully did during those lost 13 years, we might produce a reason for his move to the Granite State.[ix]

It’s worth noting here that when McCully appeared in Goffstown, he was unmarried. This in itself was unusual. Over 90% of the veterans of the 5th New Hampshire were married at some point in their lives. McCully appears to have been married in the Census of 1860, and it’s possible that he was married at some point during his 13 missing years. But even had he lost a wife due to death or divorce, there were strong incentives for a middle-aged laborer to remarry. One wonders in this case, then, if his marital status indicated that for some reason he was not a particularly eligible match.

A view of Goffstown Village in 1887.

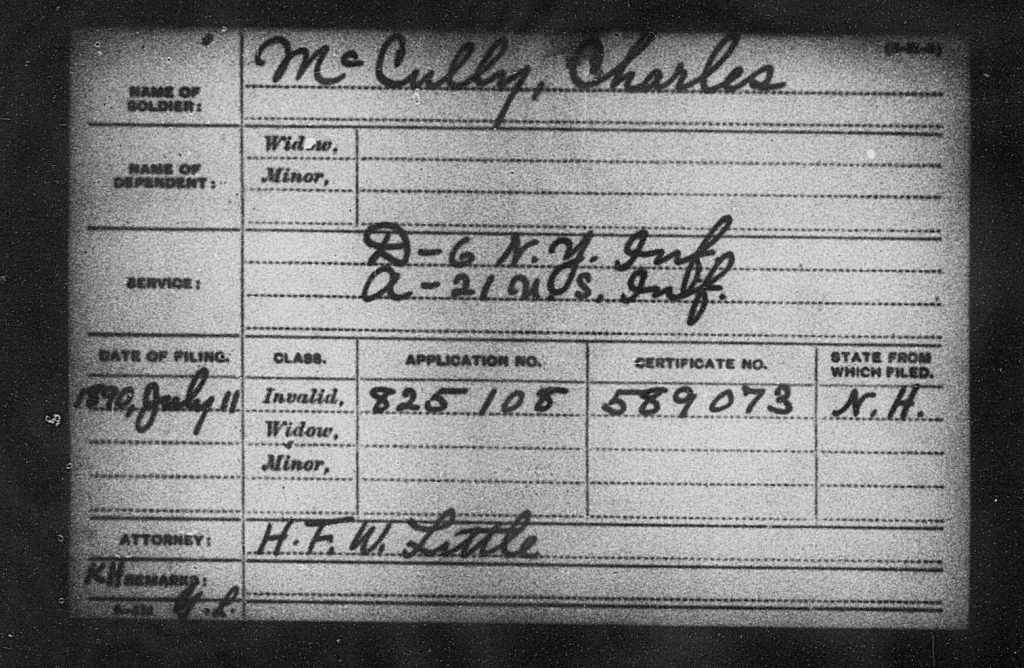

Documents from 1890 reveal something about McCully’s outlook and situation. In July of that year, he filed for a pension. In all likelihood, he had avoided doing so until this point because he was afraid that his desertion would come to light. Desperation seems to have overborne his caution because his entry in the Veterans Census of 1890 indicates he was a “Pauper.” For obvious reasons, his pension index card listed his service with the 6th New York and the 21st US Infantry but left out his time with the 5th New Hampshire. A number of veterans played this game with the federal government—some got away with it, and some didn’t. But this game came at a cost; in angling for a bigger payment, McCully could not refer to the wound he had suffered at Cold Harbor while serving with the 5th New Hampshire. His entry in the Veterans Census also listed his service with the 6th New York and the 21st US, but left the 5th New Hampshire out. Under “Disability Incurred,” one finds “Rupture [Hernia] General Disability.” There is nothing about the wound from Cold Harbor.[x]

Charles McCully’s pension index card from 1890. Note that he did not refer to his service in the 5th New Hampshire. Henry F. W. Little (1842-1907), McCully’s pension attorney, won the Medal of Honor for heroic service on the picket line in September 1864 while serving with the 7th New Hampshire in front of Petersburg, VA. Little later wrote The Seventh Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (1896).

The Census from 1900 does not list an occupation for McCully, and one wonders if his disability was such that he depended entirely on his pension. In any event, McCully did not have long to live. He appears to have contracted melanoma which chewed away at his face. He spent his last several months, no doubt in great agony, at the Hillsborough County Hospital in Goffstown where he died on May 9, 1903.[xi]

Obviously, it is difficult to track marginal folks like McCully through documents. People like him did not want to be found until they were ready. In the meantime, nobody tried too hard to locate them. Folks in this position often left behind many mysteries. Some can be resolved with more research. For example, if I had the time to look through the 6th New York’s records, I could probably find out why McCully was reduced to the ranks from sergeant. Or, perhaps with a little more mental elbow grease, I could determine what happened to McCully between 1867 and 1880. Bringing obscure figures like McCully back to life is not just an exercise in antiquarianism, interesting though the process may be. Rather, it helps us understand how the “other half” in a regiment—the deserters, shirkers, malingerers, thieves, and even rowdies—lived both during and after its service. For obvious reasons, these types of soldiers have not made the same mark on the historical record as others. But their experiences are just as much a part of soldiering as anybody else’s.

So there are mysteries, and they are a bit difficult to clear up, but they are worth illuminating. I’ll leave you with one that some of the more attentive among you may have already noticed. It is probably the type of question that we can never answer for sure. The 5th New Hampshire was widely recognized as a storied unit, and literally hundreds of its veterans proudly proclaimed their service in the regiment through inscriptions on their headstones. Charles McCully, however, was an Empire City man, born and bred. He served in the field with the 5th New Hampshire for a mere five months. After he was wounded at Cold Harbor, he deserted. For that reason, after 1864, he did everything he could to conceal his service in the regiment. Yet, “Co. G 5 REG. N.H.V.” remains engraved on his tombstone to this day. How or why this occurred will probably remain unknown. But perhaps it provides us with insight into how some of those among the “other half” may have viewed their service with a famous regiment.

[i] https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011525055&view=1up&seq=273

[ii] “United States Census, 1860″, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MC7R-7X8 : 18 February 2021), Charles Mc Cully, 1860.”United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MC7R-7X8 : 18 February 2021), Charles Mc Cully, 1860.

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6th_New_York_Infantry_Regiment

[iv] https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/application/files/4515/5058/8660/6th_Infantry_CW_Roster.pdf

[v] A “Drayman” was someone who drove a dray, that is, a flatbed wagon. This description matches well with his occupation in the Census of 1860, which was a “Carman.”

[vi] “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q27M-9MBF : 16 March 2018), Charles Mc Cully, 09 Dec 1863; citing Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Rockingham, New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,316,447.

[vii] “New Hampshire, Civil War Service and Pension Records, 1861-1866,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QLM8-CY5M : 16 March 2018), Charles H Mccully, 09 Dec 1863; citing Portsmouth, Rockingham, New Hampshire, United States, New Hampshire Secretary of State, Division of Records Management & Archive; FHL microfilm 2,319,539.

[viii] His occupation was listed again as “Carman.” “United States Registers of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VRQ8-HSV : 12 March 2018), Charles Mccully, 23 Sep 1865; citing p. 224, volume 60, Fort Hamilton, , New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication M233 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 30; FHL microfilm 350,336.

[ix] “United States Census, 1880,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MHRF-NTW : 14 January 2022), C. Worley McCully in household of Franklin Tucker, Goffstown, Hillsborough, New Hampshire, United States; citing enumeration district , sheet , NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm .

[x] “United States General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KDBC-BRC : 20 February 2021), Charles Mccully, 1890; see also “United States Census of Union Veterans and Widows of the Civil War, 1890,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K837-1NF : 8 March 2021), Charles A Mccolley, 1890; citing NARA microfilm publication M123 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 338,199.

[xi] “New Hampshire Death Records, 1654-1947,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FSNT-FHZ : 22 February 2021), Charles Mcculley, 09 May 1903; citing Grasmere, Hillsborough, New Hampshire, Bureau Vital Records and Health Statistics, Concord; FHL microfilm 2,110,576. See also https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/144382470/charles-c-mccully.